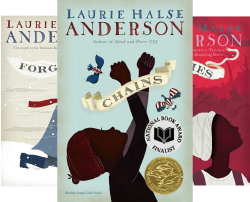

Laurie Halse Anderson’s award-winning YA novels set during the American Revolution are superb. Not only does she get her history correct — with fascinating detail about daily life for wealthy and working classes, Loyalists and Patriots, city life and army camp life — but she also provides narrators whose perspectives are unique and provocative. Isabel and Curzon are slaves. Each brings a different view of the revolution and what it means for them as slaves. The three novels take the reader from May of 1776, when the British are about to invade New York, through the harsh winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge, and then autumn of 1781 at Yorktown. While dealing with the forces of history and the scourge of slavery, Isabel and Curzon will discover what revolution means for them personally and whether they and their friendship can survive.

Laurie Halse Anderson’s award-winning YA novels set during the American Revolution are superb. Not only does she get her history correct — with fascinating detail about daily life for wealthy and working classes, Loyalists and Patriots, city life and army camp life — but she also provides narrators whose perspectives are unique and provocative. Isabel and Curzon are slaves. Each brings a different view of the revolution and what it means for them as slaves. The three novels take the reader from May of 1776, when the British are about to invade New York, through the harsh winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge, and then autumn of 1781 at Yorktown. While dealing with the forces of history and the scourge of slavery, Isabel and Curzon will discover what revolution means for them personally and whether they and their friendship can survive.

In the first novel, Chains, Isabel serves as our narrator. She is about 12 and her sister Ruth is about 5. They live in Rhode Island and have been slaves, but their mistress has died and according to her will, Isabel and Ruth were to be freed upon her death. Her unscrupulous nephew, however, refuses to track down the copy of the will and sells the girls to a family of British Loyalists. They are shipped off to New York, where their mistress Mrs. Lockton, abuses Isabel and treats Ruth as if she were a living doll. Isabel’s main concerns are for her little sister, who is prone to seizures and has some sort of intellectual disorder (perhaps a mild form of autism), and gaining their rightful freedom. Shortly after arriving in New York, a city divided between Patriots and Loyalists and where slavery is common and accepted by both sides, Isabel meets Curzon, a slave in the employ of the Patriot sympathizer Bellingham. Curzon convinces Isabel that by spying on the Locktons, who are important in Loyalist circles, and reporting to the patriots, she will win her freedom. Isabel is wary, but eventually decides to collaborate with the Patriots. Yet after taking great risks, the patriots do nothing for her and Ruth, and after a series of tragic events, the sisters are separated. Meanwhile, Curzon has joined the patriot army, and after New York falls to the British army, he is incarcerated in the local jail under atrocious conditions. At the end of the book one, Isabel finds a daring way to free herself and Curzon, and they take off from New York together but with very different goals in mind.

The second novel, Forge, is narrated by Curzon. As it begins, we learn that he and Isabel have split up under less than amicable circumstances. Curzon is headed north and encounters a skirmish between Patriot and British forces. He joins up with the Continental Army and befriends a fellow soldier named Eben. Curzon cannot tell anyone that he is in fact a fugitive slave, but then again, his master Bellingham had promised Curzon freedom for fighting on behalf of the Patriots. Most of the others in his regiment seem fine with Curzon; he’s a good fighter and saved Eben in the skirmish. But there is racism in the ranks, and one fellow soldier takes a distinct dislike to Curzon and goes out of his way to make life miserable. Meanwhile, the Patriots are on the way to Valley Forge for winter camp, where conditions are miserable. The winter is unusually harsh and supplies are few and far between. Soldiers lack food, clothing and shelter. Anderson’s descriptions of camp conditions are vivid and historically accurate. As if this weren’t enough of a trial, Curzon’s master Bellingham arrives at the camp and recognizes his slave. Curzon is forced back into slavery at Bellingham’s personal quarters, not far from Valley Forge. But an even bigger surprise awaits there — Isabel! She has also been re-enslaved and even must wear an iron collar because she has tried to escape so many times. Isabel and Curzon have a rather tense reunion and will need time to work out the issues that divided them. The one thing they seem to agree on is that they have to escape. The question is not just how, but which side do you support? From Isabel’s point of view, neither the British nor the Patriots really care about the plight of slaves. Each side promises freedom in exchange for support but doesn’t deliver. Curzon truly believes in the Patriot cause with its ideals of freedom and equality.

Book three, Ashes, picks up in 1781 and is narrated by Isabel again. She and Curzon are together but their relationship is still strained. He wants to return to fighting for the Patriots but he has agreed to go south to help Isabel track down her sister Ruth, who would now be 12 years old. Ashes focuses on Isabel’s troubled relationships with Curzon, Ruth and the revolution. She is still uncommitted to a side; instead, she is committed to herself and Ruth. Yet, at the battle of Yorktown she will have to make up her mind about Curzon and the revolution, and she will gain a deeper understanding of her sister. Anderson does an amazing job of describing not just the state of the armies at Yorktown and their strategies, but also camp life and the role of camp followers. At Yorktown, we see an all black regiment fighting for the Patiots, we learn that the British used small-pox infected slaves as a form of biological warfare against the Patriots, and that even after victory, some of our Founding Fathers were resolved to track down and punish their own runaway slaves.

Anderson’s trilogy has many strengths and is worth reading yourself and as well as putting in the hands of your school-age kids. First, I applaud the historical accuracy. Each chapter begins with a short blurb from the time: quotes from those who participated in the events of the revolution, quotes from letters and newspapers, from British and Patriots, males and females, black and white. Ashes contains an appendix with a Q & A with Laurie Halse Anderson in which she addresses questions of fact vs fiction and provides suggestions for further reading. Anderson’s books are filled with fascinating details regarding every day life, such as what a trip to the market might look like, how cleaning and washing were done, what preparation for a fancy party might be like. Daily life for a slave in New York, and especially the punishments meted out to them, are also provided in detail. Isabel’s punishments from Mrs. Lockton are horrific and were generally accepted as appropriate. Anderson also includes detail about historical events that might barely be mentioned in a history book: the battle and surrender of Patriots in New York, the fire that devastated that city.

Anderson gives an unflinching view of whites’ treatment of slaves and freed men as well. In all three novels, we see examples of whites (Loyalist and Patriot) who know how to use the system to their advantage. The law was not there to protect slaves versus their masters, nor did it protect freed slaves from being rounded up and sold back to slavery. While there were Patriots and British who abhorred slavery, I think we all know that our founding fathers were loathe to give up their own slaves, at least not until they themselves had died and wouldn’t suffer from the loss of slave labor. Yet Anderson does more that just show an obvious pro- and anti-slavery sentiment. She also creates white characters whose racism is a bit nuanced. In Chains, Lady Seymour is a Loyalist who is appalled at Isabel’s treatment. Near the end of the book, she tries to explain herself to Isabel, saying that she hated what had happened to Isabel and Ruth, and that she had tried to buy the girls from Mrs. Lockton but failed. Lady Seymour says the girls would have suited her household. Isabel doesn’t know what to say to this and thinks,

It would have eased her mind if I thanked her for wanting to buy me away from Madam. I tried to be grateful but could not. A body does not like being bought and sold like a basket of eggs, even if the person who cracks the shells is kind.

Curzon encounters a similar racism from his friend Eben. He asks Eben why, if we are fighting for freedom, do some people on our side get to own other people? Eben’s reply is that we’re fighting for our freedom, not theirs, and then he quickly adds that his family doesn’t own slaves. Curzon pushes him further, pointing out that their colonel owns slaves and what would happen if they ran? Eben replies that they would be breaking the law. When Curzon asks if an unjust law isn’t meant to be broken, Eben becomes irritated and upset. He says,

Now you are spouting nonsense. Two slaves running away from their rightful master is not the same as America wanting to be free of England. Not the same at all.

While Curzon and Eben’s friendship seems over after this conversation, Eben eventually becomes enlightened and realizes he was wrong.

Anderson does an outstanding job throughout these novels of showing how the revolution might look from the perspective of those who longed for freedom and equality but for whom it was not fought. Isabel comes across as a pragmatist and realist from the beginning. She learns early that you cannot trust either side to fight for you (slaves). Curzon is the idealist until just after Yorktown, when some of his illusions about the revolution are shattered. Yet these characters have had to fight all their lives just to stay alive and try to be free; they were born in the colonies and so this is their country, too. They seem to have a sober grasp of reality — that they could easily lose what they have gained, but perhaps this is the best chance they have. I would say the ending is optimistic, but given what we know of the treatment of slaves and freed men in the decades following the revolution and the Civil War, the ending is also perhaps an admonition to the reader to consider how our history has been written, how our stories have been told, and whose voices are missing.