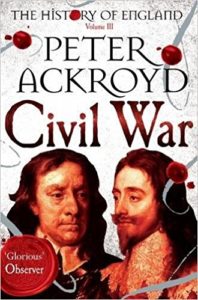

I thoroughly enjoyed this, the third volume of Peter Ackroyd’s History of England, which covers a period of our history that I knew virtually nothing about (I don’t think I can really count Horrible Histories’ Charles II song as ‘knowledge’), from the succession of James I following the death of the childless Elizabeth I through to the flight of James II, taking in the civil war and the unprecedented execution of a king that happened in between. Here’s what I learned…

James I of England, also James IV of Scotland, was the first Stuart king, uniting the English and Scottish thrones. Different in every way to his predecessor except for his tendency to prevaricate, James’ court was a rather licentious one. No stranger to scandal, James I spent money like it was water and was often rather drunk, as well as rumoured to be homosexual due to his obvious affections for his favourites (particularly the baby-faced Duke of Buckingham). Believing that kings had the divine right to rule, James’ relationship with Parliament was often strained by his attempts to impose his will, as well as by his constant demands for more money through the raising of taxes. During his reign, religious tensions between the various factions of Catholics and Protestants (and the many other sects in existence) would worsen as he sat on the fence, placating one group and then the other to no-one’s satisfaction. Some of these tensions would come to a head – it was during James’ reign that the Thirty Years War started and the Gunpowder Plot was thought up and discovered – while others would simmer until the reign of his son, who succeeded him in 1625.

Charles I was a more severe man than his father, differing from him in every way save for his constant fights with Parliament over his belief that he should be supreme ruler, with them answering to him rather than the other way around. Parliament would soon come to be seen as representing the voice of the people against a corrupt king, who constantly tried to raise new taxes to finance his many attempts at war (most of which ended in humiliation) and dissolved Parliament whenever they wouldn’t do what he wanted, which gave him an increasingly despotic air. This would culminate in Parliament going so far as to lock themselves into their chambers against his soldiers, with Charles retaliating by arresting various members, while they passed laws that went against his interests. Parliament eventually managed to curb Charles power, appointing their own army and seizing control of his armouries, whilst also proving to be just as bad as him when it came to raising taxes and religious persecution (a common punishment of the time for those who Parliament felt were believing in God wrong was for their ears to be cut off and their faces branded, with at least one prisoner so badly maimed that on leaving prison he was no longer able to see, hear or walk). No longer representing the people but having become despots themselves, citizens could be imprisoned for simply saying that Parliament didn’t have the king’s consent. A series of battles took place between the King’s forces (already known as Cavaliers) and those of Parliament, with the latter finally claiming victory under the command of one Oliver Cromwell and his New Model Army. Having been taken hostage by the Scots, to whom he’d fled after his losses, Charles was sold back to Parliament for the sum of £400,000. Refusing to compromise on a deal where he would remain a figurehead whilst Parliament ruled, Cromwell declared him an enemy of the state and, after a loaded trial, Charles was sentenced to death and a resolution passed barring any successor to the throne. A new constitution was written, with Cromwell styled as ‘Lord Protector’ and given more power than was originally held by the king, and England was turned into an even more miserable place with laws passed to ‘improve’ public morale, including the banning of Christmas, drunkenness, plays and gambling, and with even travelling on the ‘Lord’s day’ seeing you liable to be put in stocks or a cage. While he’d lost public sympathy with many of these new measures, Cromwell ruled until his death, naming his son Richard as his successor.

Richard Cromwell, however, had no appetite for rule and when the usual squabbles arose – people were still arguing that others were believing in God wrong (and still are) – he abdicated in an attempt to avoid bloodshed, leaving the way clear for Charles II’s return to England (having spent the time since the death of his father, Charles I, wandering Europe) and ascension to the throne.

Seen as an affable figure, Charles II’s return was greeted with jubilation, with ‘the Merry Monarch’ declaring a general pardon for all treasons committed in the recent past save for those who signed the death warrant for this father. Surrounded by a circle of ‘wits’, his court became a scandalous one, with their purpose seeming to be to make as much money for themselves as possible (which suited Charles as it made them far more easy to manipulate for his own ends) and with the king devoted to pleasure – by 17 of his known mistresses he had 13 illegitimate children although his wife, Catherine of Braganza, would never manage to bear him a child. With his reign taking in a bout of the Black Death (where as many as 10,000 fatalities were listed each week) which eventually abated thanks to the Great Fire of London, and a trade war with the Dutch, plots once again arose to overthrow the king in favour of a monarch more suited to whichever religious group was currently doing the plotting – the Catholics preferred the king’s brother, James (who had converted to Catholicism) whilst the Protestants preferred Charles illegitimate son, the Protestant Duke of Monmouth. On Charles’ death following a period of ill health, his brother became James II, but not for long. James attempted to reassert the rights of Catholics in England and, with the Duke of Monmouth having been beheaded, various earls started writing to William of Orange (grandson of Charles I through his daughter and husband of daughter of James II), inviting him to invade and seize the throne. With the lords having deserted him, James fled England for France where he would spend the rest of his life, leaving William of Orange free to claim the abdicated throne for himself.

As well as taking in all of the above, Ackroyd also makes sure to include what life was like in general during these years, encompassing the changing fashions, leaps in architecture and scientific knowledge thanks to figures like Christopher Wren and Isaac Newton, and the changing moods in music and literature from the likes of Shakespeare, John Milton and Samuel Pepys. He’s been a great guide so far, and I’m pleased to have already been bought the fourth volume of this work, fleshing out the histories that I’d only previously known of through Blackadder and the aforementioned Horrible Histories (one of the greatest TV programmes ever made, even if it’s supposed to be for kids). If you’re at all interested in finding out the history of our small island, Ackroyd is a must-read.