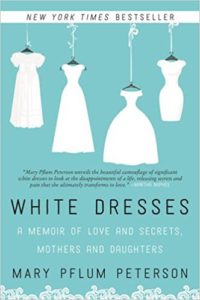

This was one of those books that I thought I was going to like but just couldn’t fully get into. In this memoir, Mary Pflum Peterson, a former CNN reporter and current Good Morning America producer, uses a series of white dresses to anchor a set of stories about herself and her mother, Anne Diener Pflum. We read descriptions of baptismal outfits, communion dresses, and wedding gowns, but we also learn about the lives of these two women—their joys and a lot of their sorrows.

This was one of those books that I thought I was going to like but just couldn’t fully get into. In this memoir, Mary Pflum Peterson, a former CNN reporter and current Good Morning America producer, uses a series of white dresses to anchor a set of stories about herself and her mother, Anne Diener Pflum. We read descriptions of baptismal outfits, communion dresses, and wedding gowns, but we also learn about the lives of these two women—their joys and a lot of their sorrows.

It’s an interesting structure that gets annoying after a while—each chapter begins with a “created” scene involving a white dress, and then Peterson backtracks and tells the story, more traditional memoir style, of the events leading up to and stemming from that moment. As a reader, I felt much more interested in Anne’s story; she grew up in a strict Catholic family in Indiana and worked hard for (but never seemed to get) her mother’s approval. She struggled with depression but was still able to leave her small town and go to college. However, a difficult break up and another bout of depression led her to the convent for a time.

These experiences plant the seeds for future problems even as Anne marries, moves to Wisconsin, and becomes a devoted and caring mother, who strives to give her two kids the love and support she felt she lacked growing up. Both mother and daughter face challenges over the years and Peterson does a good job of showing how the problem of her mother’s hoarding starts small but grows into a condition with devastating consequences.

Still, I have to say I found Mary Pflum Peterson less interesting, and I found myself skimming over stories of her love of frilly dresses, her incredible adventures as a young reporter for CNN, and her dating life*. As Mary grows older, changes jobs, meets her husband, and begins to have a family, her mother’s condition becomes worse and the family home becomes a prison for Anne, one that she feels she can’t leave or let people into.

The memoir begins and ends with the same event—Mary carefully working her way through teetering piles of stuff in her mother’s home, after her mother has died, hoping to find these important white dresses—that stand for powerful moments in both their lives. I understand Mary’s urge to recover these dresses even as I am kind of dismayed by it and that’s a good analogy for how I felt about the whole book.

*I think it’s this passage that really made me want to throw the book at the wall (or maybe at Peterson):

But while I was showered with gifts by the men in my life, it wasn’t because of any sexual favors I was granting them. On the contrary. I was a chaste girl, seldom granting any man, even those who begged loudest and longest or who spent the most money on me, much more than flirtatious smiles, good-night kisses, and, on occasion, some fiercely fun dry humping. To be crystal clear: I was a virgin. And I wanted to remain a virgin. (p. 188)

Let’s be clear. I have no problem with someone deciding they do not want to have sex for religious reasons (or for any reasons) because that’s totally their choice. However, instead of any in depth thinking about how this decision relates to her own Catholic faith or that of her mother, we simply get that she wants to be a good Catholic girl. When she finally has sex two years into a relationship with “Steve,” it’s only because “there’s only so much begging a girl could take.” This whole section of the book made me so profoundly annoyed and uncomfortable that I almost stopped reading (but because it was a book club book I slogged on).