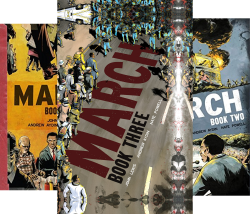

The March Trilogy, winner of the 2016 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, is a first-hand account of the civil rights movement in the United States as told by one of its leaders, Congressman John Lewis of Georgia. These graphic novels span the years 1960-65 and are presented as John Lewis’ recollections on January 20, 2009 — the day of President Obama’s first inauguration. This is an amazing memoir that is not only accessible to young readers, but would most likely be an eye-opener to many adults. Even if you think you know about the civil rights movement, John Lewis’ account provides vivid and personal details about the inner workings of the various organizations that were devoted to the promotion of the rights of people of color and about the horrific violence enacted by white authority and average citizens against those who participated in peaceful democratic demonstrations. Now more than ever, we need to be reminded of our ugly and shameful history and of who the true heroes of modern American democracy are.

The March Trilogy, winner of the 2016 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, is a first-hand account of the civil rights movement in the United States as told by one of its leaders, Congressman John Lewis of Georgia. These graphic novels span the years 1960-65 and are presented as John Lewis’ recollections on January 20, 2009 — the day of President Obama’s first inauguration. This is an amazing memoir that is not only accessible to young readers, but would most likely be an eye-opener to many adults. Even if you think you know about the civil rights movement, John Lewis’ account provides vivid and personal details about the inner workings of the various organizations that were devoted to the promotion of the rights of people of color and about the horrific violence enacted by white authority and average citizens against those who participated in peaceful democratic demonstrations. Now more than ever, we need to be reminded of our ugly and shameful history and of who the true heroes of modern American democracy are.

The first book of March covers John Lewis’ life until April of 1960. From his childhood in rural Pike County, Alabama, Lewis was drawn to the church and preaching and had a great desire for education. A trip up north with a relative opened his eyes to the difference in the lives of blacks in the north versus the south, and between the lives of whites and blacks. Inspired by the preaching of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the activism of people like Rosa Parks who led the bus boycotts, Lewis attended theological college in Nashville and got involved in the movement for peaceful resistance. Lewis, Aydin and Powell do a wonderful job in this part of the book showing how one prepared oneself for nonviolent resistance as inspired by Gandhi. Those who participated in sit-ins at lunch counters had gone through extensive preparation to get ready for the verbal and physical abuse that would follow. Some of the trainees dropped out of the program, knowing that they would not be able to put up with the stress of being screamed at and beaten without fighting back. And this is exactly what happened; those who conducted sit-ins were physically beaten, verbally abused and even sent to jail, where indignity piled upon indignity. The courts that tried these young people were unjust in their treatment, but John Lewis and the other demonstrators would not back down. In fact, the popularity of the demonstrations increased as news of them spread, and people like John Lewis jumped back in as soon as they were released from jail.

Book 2 covers the years 1960-1963, when John Lewis was still a student and one of the leaders of the Student NonViolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Sit-ins at lunch counters continued, as did stand-ins at other businesses such as movie theaters, and violence against peaceful protests also continued. But rather than back down or hold steady, the movement pushed forward into new areas. In 1961, Freedom Riders began to test the Supreme Court decision Boynton vs Virginia. This court decision outlawed segregation on buses and at terminals, but no one was enforcing the law and discrimination continued. Freedom Riders, including many students and activists from the north, both black and white, were trained for an organized campaign to put Boynton to the test. In particular, they tried to ride to Birmingham, Alabama (an area Lewis calls “the black belt” of the south). Freedom Riders were stopped, arrested, driven out of town, even killed; buses to Birmingham were canceled in order to stop them from riding. Many riders went to jail, and violence against people known to support the desegregation movement escalated. People’s homes were shot at and churches were firebombed. Even though courts upheld the right of Freedom Riders to do what they were doing, state and local authorities (mayors, governors, chiefs of police, sheriffs, etc.) stopped these people from exercising their rights and supported the violence committed against them. But the work of non-violent protestors was making the national news more and more, especially since white students who supported the movement were being abused equally with black people. John Lewis notes that while the civil rights movement was growing, it was also changing. Maintaining discipline in the ranks and ensuring peaceful protests became more difficult, and among civil rights groups divisions grew. More traditional organizations such as the NAACP wanted SNCC to back off and take a breather from demonstrating, particularly as it seemed the President Kennedy and his brother Robert (attorney general) were sympathetic to the cause. Some, such as Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) wanted to change the focus from freedom rides and marches to voter registration (RFK had suggested this). But Lewis and the SNCC continued their fight, while the new governor of Alabama George Wallace promised, “Segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” In 1963, JFK promoted a civil rights bill that, in the opinion of many including John Lewis, did not go far enough because it did not guarantee the right of all African Americans to vote. Division among civil rights leaders came to a head at the time of the March on Washington (August 1963). John Lewis was prepared to give an incendiary speech about the civil rights bill but was prevailed upon by moderate forces to tone it down for the march. Most people think of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech when they think of the march on Washington, but John Lewis gave a powerful speech as well, reprinted in full in this tome.

Book 2 ends and Book 3 begins with the horrific firebombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama on September 15, 1963, which killed four little girls. This final volume takes the reader into 1965, when the voting rights act was passed. In book three, we see activists like John Lewis and Fannie Lou Hamer, among many others, engaged in the Freedom Vote movement to register black voters. As with every other peaceful and lawful civil rights movement in the south, this one was met with anger and violence from white power and with obstruction of justice, and more and more often the press was there to document it. Division within the civil rights community also continued as the NAACP argued for a stop to demonstrations, but SNCC felt the need to continue demonstrating and marching. A further complication was the national political situation. A presidential election was coming up in 1964, and President Johnson was worried about losing the support of southern states. The SNCC was demanding that black delegates be seated at the democratic national convention since segregation and racism were obstructing the rights of blacks in states like Mississippi and Alabama. One of the highlights of book three is the coverage of party conventions in 1964, particularly the speech given by moderate Republican Nelson Rockefeller about the dangers facing the GOP (in the form of a radical, well-financed minority) and the televised speech by Fannie Lou Hamer, detailing the abuses that she personally had faced in trying to register to vote. But the most important event of Book 3 is the March on Selma on March 7, 1965, aka “Bloody Sunday”, which involved a violent confrontation on the Edmund Pettus bridge. John Lewis nearly died from the beating police inflicted on him. Once again, however, this brutality served to win sympathy and support for the cause of African Americans in the south. President Johnson finally made a public statement acknowledging the need to address the “American problem” of racial injustice in the south.

The march on Selma was successfully completed two weeks later. In 1965 the voting rights act passed congress. Yet, as Lewis shows and we should know, this did not solve our American problem. Even with the election of the first African American president, which is where Lewis ends his story, we still have to work to make sure that democracy and equality are extended to all. We live in times when civil rights for many marginalized groups are under threat, but John Lewis and the brave men and women of the US civil rights movement have shown us what to do and how to do it. Stand firm, stand up when you’re knocked down, hold on to your principles. Use your voice and your whole body to make good trouble. Absolutely put these graphic novels in the hands of your kids and read them yourself, too.