Like most non-fiction books I pick up, this choice started with listening to Terri Gross interviewing Bronwen Dickey on Fresh Air last year. I remember both being fascinated by the discussion about pit bulls, which at the turn of the century were considered classic family dogs, and by the stories Dickey told about growing up in a household that involved both dogs and a famous parent with addiction issues. This fall, I worked with a former student several times in the writing center as she did research for a paper about discrimination against pit bulls. She listened to the audio version of this book and used several of Dickey’s points to bolster her argument that pit bulls were unfairly targeted as a dangerous breed.

Like most non-fiction books I pick up, this choice started with listening to Terri Gross interviewing Bronwen Dickey on Fresh Air last year. I remember both being fascinated by the discussion about pit bulls, which at the turn of the century were considered classic family dogs, and by the stories Dickey told about growing up in a household that involved both dogs and a famous parent with addiction issues. This fall, I worked with a former student several times in the writing center as she did research for a paper about discrimination against pit bulls. She listened to the audio version of this book and used several of Dickey’s points to bolster her argument that pit bulls were unfairly targeted as a dangerous breed.

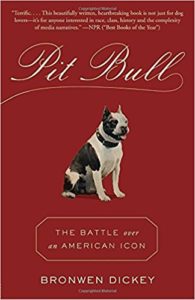

Flash forward a few months to when I saw this book in a display at my community college library and nabbed it. The book ended up being even more interesting and timely than I could have imagined. That is, in exploring how pit bulls’ reputations have risen and fallen over the last century and a half, Dickey is telling a larger story that connects to class, race, constructions of identity, and the power of the media.

For example, I would love to use a chapter called “Looking Where the Light Is” to help Comp 1 students think about information literacy. In it, Dickey discusses how one employee of a Long Island Sheriff’s department, Karen Delise, began questioning the way the media seemed to be making judgments on what they called “killer breeds” based on limited evidence. Her research led her to identify some huge holes in the existing “proof” about pit bulls and other breeds being dangerous—data that called into question many legal and medical claims:

The lack of a scientific foundation for the claims made about pit bulls in the press, in medical journals, and in courts of law is deeply disturbing. Jeffrey Sacks likened dog bit research to the well-worn joke about the drunk trying to find his keys in a darkened parking lot. Another man comes out, sees the first one crawling around on his knees, and asks what he is doing. The first man says, “I’ve lost my keys. I can’t find them!” The second says, “Well, where were you when you dropped them?” The first points to the far side of the lot and says, “Over there.” “Over there?” the second man says. “Then what are you doing all the way over here?” The first man points up to the streetlamp and replies, “I’m looking where the light is.” (89-90)

Having just seen the documentary, Thirteenth, and started to read The New Jim Crow, it’s not hard to see the parallels between a media that constructs a certain breed of dog as naturally vicious and a media that constructs certain groups of people as “super predators” or “law breakers who are ruining America.” Dickey tells the story that in the 1870’s, a rabies outbreak in New York City was linked in the media to the breed of dog called Spitz (now called Pomeranians). That is, no one seemed to make the connection between the popularity of the dog and the number of rabies cases and human bites but instead doctors at the time suggested that certain breeds of dogs carried the virus. As a result, there was what was called the Spitz panic and Spitzes were destroyed in record numbers and in horrible ways. What is fascinating here is that pit bulls are not the first dog to be targeted in a breed focused way but rather they are one breed in a long line of breed panics. This is especially problematic because Dickey does a great job in showing both how fuzzy the concept of “breed” is in the world of dogs but also how misidentified actual pit bull terriers are.

If you love dogs or even if you don’t, this book is a fascinating read because it connects the complex world of canines to the even more complex (and dysfunctional) world of humans.