This was a marvelous biography of an iconic American who’s life coincided with some of the most tumultuous and divisive events in American history. But I find myself struggling to review it.

This was a marvelous biography of an iconic American who’s life coincided with some of the most tumultuous and divisive events in American history. But I find myself struggling to review it.

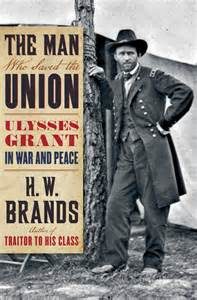

H.W. Brands doesn’t skimp on the details. His Ronald Regan biography tips the scales with more than 800 pages. His book on FDR is even more ambitious, being close to 900 pages – though, when you consider that FDR had nearly twice as much time in office as Regan, it may be said that not enough space was provided for his biography. Well, Brands continues the practice, here, with 718 pages of text on Ulysses Grant and his era. It’s a fascinating read, and thorough in its exploration.

The thing I was most struck by is how quintessentially American the story of Grant is. Had his presidency not been plagued by ties to corruption, he might have gone down as one of the most historical American characters in history. Through the first half of his life, he struggled to overcome failure, poverty, and personal weaknesses that would’ve ruined a lesser man. He was an unimpressive student at West Point, and though he achieved some notoriety in the Mexican-American war, his experiences didn’t translate to a great deal of career advancement. He was first stationed in New York, but was then transferred to the Pacific Northwest to help keep the peace between settlers and American Indians. In what seems odd, today, his route there took him to Panama, where he had to make an overland trek before catching ship northward. While there (first Oregon, then Washington), he quickly realized that most of the conflict was caused by white settlers, not the Indians. He spent years in the Pacific Northwest, without his family and with little income. To supplement his salary, he made numerous attempts to start-up various business ventures (including farming), and failed at every one. In 1853, he was transferred once again, this time to California. Still without his family, and having a son he had never seen, Grant began drinking. Within two years, this led to his ultimate resignation from the military and admittance to civilian life at the age of 32. With neither job, nor prospects, he made his way back to his family and set up life in St. Louis…..where he continued to fail at everything he attempted to do. And there he stayed, failing and being miserable, with an ambitious wife and gaggle of children, until war broke out once again in 1861. With some trepidation, Grant signed up for service to the Union (despite living in Missouri), and within 4 years, his stature among his countrymen was surpassed only by Abraham Lincoln.

How many figures in American history have gone from being unknown to the world while having no career path at the age of 39, to being hailed as perhaps the second most important person in the country by the age of 43? It’s quite a meteoric rise.

April 14, 1865, a mere two weeks following his ultimate victory at Appomattox, Grant was in Washington to attend a cabinet meeting with the president. Anxious to travel to New Jersey with his wife, the Grants turned down the First Lady’s invitation to attend the theater that night. We will never know what would’ve happened had they chosen instead to join the Lincolns. It may have been that he, himself, would’ve also been assassinated. It may also have been that he could have prevented Lincoln’s death. But it is almost certain that American history played out different for the events of that night. The next four years saw the nation still at war with itself, this time within the federal government, itself. Andrew Johnson’s failure of an administration drew Grant into politics to a degree that he had neither planned for, nor wanted, and he actually played a role in Johnson’s impeachment. According to Grant, there was a misunderstanding about his willingness to take on the role of Secretary of War, but Johnson removed Edwin Stanton from the position with the intention of putting Grant in his place. This move violated the Tenure of Office Act, which was the cause for Congress impeaching Andrew Johnson.

In 1868, Ulysses Grant won the presidency with 73% of the electoral college in a landslide rivaled only by Donald Trump’s 57% (it was a great victory – just great. The best). And 82% four years later (suck it, Trump). But the victory was misleading. Grant wasn’t the first person to ride military victory into the White House. George Washington himself is the most obvious example. But Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison, and John Tyler (who didn’t actually fight in the War of 1812, but organized a defense of Richmond) all used military success to attain higher office. The difference with Grant, however, was that the American South was a conquered foe, with its land occupied and its spirit unbroken. Grant won a military victory only, he didn’t win the hearts and minds of the South. Washington (et al.) defeated the British, who then left what would become the United States. Andrew Jackson defeated the British in New Orleans, ending the War of 1812, and they once again left American territory. William Henry Harrison defeated Tecumseh and broke the American Indians in the Northwest Indian War and Tecumseh’s War, but those who remained didn’t become part of the United States after the defeat. Grant ‘s task wasn’t just to ride success to greater power, but to return his defeated enemy to the Union they shed so much blood to leave.

Much is made of the corruption tied to his administration, and his greatest victory is frequently cited as breaking the back of the KKK – but his administration brought the southern states back into the fold in a way that Johnson’s didn’t quite manage (even if they came back unwillingly, at times). Grant had to occupy the south throughout the later half of the 1860s in response to fears of insurrection, but during his administration, he began drawing down troops in the southern states. Votes were held, Reconstruction was at least attempted before later administrations abandoned it altogether, and Grant created the Justice Department to ensure black rights were enforced. In a nation that was quickly wanting to put the Civil War behind them, Grant was at least trying to put the country back on the right path.

It’s hard to overestimate how important this era is. Despite the numerous problems there were with reconstruction, this era is vital to American history. Perhaps more than any other. Ulysses Grant was at the center of it all: from the expansion westward through the theft of Mexican land, to the entanglement with native peoples, to the sharp division that tore the country apart, and finally with the tumultuous decades of it being haphazardly stitched back together. It was on his watch that corruption became a key issue, and the populism movement that would eventually give rise to Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson and, eventually, Franklin Roosevelt was born.

Ulysses Grant may not have been a great president, and he could be willfully ambivalent to some of the abuses of power. He put too much trust in too many undeserving people, and he lacked the finesse required to handle some of the more delicate policy issues of his job. But he stood strong in the nation’s worst moments, and always took decisive action.

And you know what, he kicked Robert E. Lee’s ass, while sacrificing fewer soldiers.

For those interested in the era roughly spanning 1840-1876, this book is vital.