In April, I spent a month in Istanbul, and that city was one of the most amazing places I’ve ever been. It was modern and historic, beautiful and creative, and that blend of Asian and European is something that can actually be seen. Put aside its physical beauty, and Istanbul is seriously one of the most interesting and fascinating places.

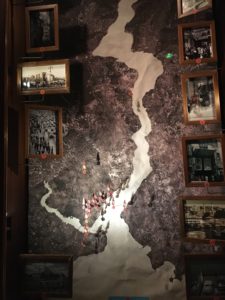

And during my last week there, I took myself to the Museum of Innocence, even though I’ve never read Orhan Pamuk’s famed book of the same name. I thought I was going to be somewhat bored during my tour of the little corner house in the beautiful neighborhood of Cihangir, but I was just so entertained. All the glass displays in the museum portray a chapter in the book in terms of the items mentioned or the moment captured. So while I have never read the book, I could sort of figure out the narrative as I strolled through it. Pamuk’s attempt — with the museum — was really to bottle what Istanbul was like during this period, through its knick-knacks and habits and events.

It was an experience unlike anything I’ve ever been to, and I left the museum feeling a sort of nostalgia for I don’t even know what. It’s like I didn’t know I missed some *thing* until it plopped itself right in my life. So I knew that I had to read the book to get all my questions about the museum answered.

The plot itself is quite straightforward. It is a love story set in Istanbul in the 70s and 80s. Kemal, a wealthy businessman from a reputable family, falls in love with a distant relative of his, Fusun, who is from the poorer, oft-forgotten part of the family tree. Despite being engaged to a woman who is deemed suitable for his social and financial status — and also being relatively content with his life — Kemal embarks on a short-lived affair with Fusun.

I’m not sure how much I want to give away, because part of the intrigue of this book is on how you never quite know what the conclusion is. Does the ending come when the affair is halted? Does it end when Kemal admits his love for Fusun to himself? Does it end when Kemal removes himself from Istanbul’s high-flying social scene?

The most frustrating aspect for me reading this was how much I disliked Kemal and yet understood where he was coming from. I suspect that might have been Pamuk’s intention — to portray a man of privilege, in every sense of the word, and to make him act like a total ass, and then regret his actions without knowing quite how to fix the situation. The second thing I suspect I’m supposed to take away from this is how women are viewed in Turkish society. The modern ones are open to having sex before marriage, but only with a man who they would eventually wed. And even as they proclaim their freedom and independence from the stodgy old-fashioned expectations of their families, their society (including these so-called independent women) also mock those who do have sex before marriage. They so rarely have any real autonomy, any real direction in their lives. And so, these women exist between putting up a bravado of strength and independence with no way of actually directing their lives and the ways they wish to be perceived.

Come to think of it, it’s not just Turkish society. And it’s not just in the 70s or 80s.

Nostalgia is a funny thing, and I got a strong sense that Pamuk wrote this in an almost sneering manner. “Look how simple life was back then, how much fun it was, how beautiful life could have been,” he appears to be saying, before slapping the reader in the face when they realize that life is still like this, and it is actually not, in fact, simple or fun or beautiful. He is making fun of the way we humans tend to look back in the past with rose-colored lenses when things are going badly in the present. We don’t even know what we’re yearning for to return, and even if we got it, it’s not what we thought it was.

Which makes it all the more ironic that I decided to read The Museum of Innocence out of some misplaced sense of nostalgia. The magic of Istanbul had seeped into my head. Even funnier is when I read the book *after* leaving Istanbul, the descriptions of the streets and the neighborhoods — all recognizable to me — made me just want to return to that perfect period in April. It’s like a cycle of yearning for a time that I’m don’t think can ever be properly re-lived.

(Apologies for the photo quality. I took them with my iPhone in a dark museum.)