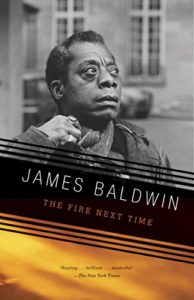

Reviewed with Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me

Reviewed with Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me

I started reading The Fire Next Time in the wake of the 2016 presidential election, reeling from the choice that my fellow Americans made and wondering where it all went wrong. Given my liberal/progressive bent, I was personally devastated and still am, and as the data came rolling in about Trump supporters, I was absolutely disgusted and enraged. Whites, including white women, went for Trump. Christians, including Catholics, went for Trump. And despite the initial assumption that it was poor rural voters who put this troll in office, the fact is, it was middle and upper class white people who did it. People who are educated, who have salaried jobs with benefits, who live in my neighborhood, go to my church and are even related to me. How does this happen? How could smart people who are “good Christians” vote for a know-nothing hater? After reading James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time and Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me, I have some sense of an answer but many, many more questions.

The two books are similar in subject matter and intention and address the question, how does a young black man live in this white world? Each writer addresses his American experience, as well as the larger, historical experience of racism and oppression directed against blacks, in a letter to a young man. In Baldwin’s case, he writes to his nephew in 1962. Coates addresses his thoughts to his teenaged son in 2014. The two writers have similar stories to tell of childhood, becoming adult and learning how to manage being black in America. For example, both men discuss the effect of racism on family relationships. They note the fear in their parents eyes throughout their childhoods. It was imperative that black children learn to be good, not just to please their parents, but to stay alive. Baldwin writes of

…a fear that the child, in challenging the white world’s assumptions, was putting himself in the path of destruction.

Black children had to learn early what the boundaries of their world were, both physical boundaries (streets and blocks to avoid) and political boundaries — what you can expect to achieve. Coates writes of a similar experience growing up in Baltimore. He notes that his parents did not spare the rod (or the belt) on him, largely out of fear of what would happen to Coates in a world that is hostile to people of color.

My father was so very afraid. I felt it in the sting of his belt, which he applied with more anxiety than anger, my father who beat me as if someone might steal me away, because that is exactly what was happening all around us.

As a parent himself now, Coates describes for his son his struggle in trying to raise him not to fear and yet to beware, particularly in a world where the black body is so expendable at the hands of authority.

…you are a black boy, and you must be responsible for your body in a way that other boys cannot know. Indeed, you must be responsible for the worst actions of other black bodies, which, somehow, will always be assigned to you.

Baldwin and Coates also discuss integration, non-violence, and the ultimate goal of life for a black person. Both men agree that the goal should never be to become like whites. Baldwin writes that he doesn’t know many people who really care about being accepted or loved by whites.

…they, the blacks, simply don’t wish to be beaten over the head by whites every instant of our brief passage on this planet.

Baldwin writes to his nephew that he has a few white friends, people with whom he would trust his life, but that when he meets Elijah Muhammad of the Nation of Islam, he has to admit that such whites are the exception to the rule of white behavior toward blacks. Baldwin was no fan or follower of the Nation of Islam but his experience of its followers and its appeal for some is enlightening.

Coates writes to his son about the Dream and not getting lost in it. The Dream is the world that white people inhabit, that can be seen on TV shows but that did not reflect the reality of Coates’s childhood. It’s a world where children are safe and don’t fear for their bodies, and people live in lovely houses with lawns and tree houses and cub scouts. Coates writes that he always sensed the barrier between his world and the Dream, and that

…the question of how one should live with a black body, within a country lost in the Dream, is the question of my life….

Baldwin and Coates describe childhoods where it would have been very easy to be drawn into crime, drinking, drugs and perhaps ultimately prison if one didn’t die first. For Baldwin, the salvation came through church. He opted to become a youth minister, and while this did keep him away from the dangers of the streets, it also opened his eyes to the hypocrisy in the church. He writes

…there was no love in the church. It was a mask for hatred and self-hatred and despair.

He felt he was

…committing a crime in talking about the gentle Jesus, in telling them to reconcile themselves to their misery on earth in order to gain the crown of eternal life.

For Coates, school was a useless, equally violent path compared to the streets until he found the Mecca — Howard University. It was at Howard that he experienced the black diaspora and had his own myths about a sort of black dream, an alternative to the Dream, shattered. Coates, like Baldwin, is a renowned and respected writer, and while his Howard education certainly led him there, his mother was the one who started him on the path. She taught him to read and write while very young, and encouraged him, when he had made mistakes, to write about them and keep asking himself “why”. This not only helped introduce basic journalism skills to her son, but it put him in a habit of “self-interrogation,” of questioning his thoughts, beliefs and actions, and this has stayed with me after the reading.

Reading these books after the 2016 election, the thing that really stood out for me and hit me between the eyes is that neither Baldwin nor Coates makes a distinction between progressive and conservative, between allies and enemies, between “good” and “bad” whites. We are all just whites, all together. The problem of racism is on all of us whites. While I may have absolved myself regarding this election, if I engage in some self-interrogation, I have to admit that some of my choices, and my complete unawareness, contribute to the racism we see. For example, where I live in southwestern PA, outside Pittsburgh, was solidly pro-Trump, including my neighborhood. Trump signs were everywhere. Why do I live here? Well, when we moved here, the location was great for the jobs my spouse and I had. We asked the realtor about taxes and schools and internet connection (it was 2001). We never once asked about integration or how racially diverse the area was. It never occurred to us. As a result, we live in a very white world. The kids’ school is also very white, of course, which means they aren’t exposed to diversity. And the flip side of the “why do I live here” question is, why don’t people of color live here? The development that we live in is enormous. There are hundreds and hundreds of homes here and I can think of exactly one family of color in the neighborhood. New developments are being built around us all the time and they are stark white. Now, the big economic draw in this part of the world is the energy industry. We sit atop the Marcellus Shale deposits, and when the rest of the US economy was struggling in the Bush recession years, this area was ok. There were lots of jobs for oil, gas, fracking…. Were people of color getting those jobs? I don’t know but my guess is no, they weren’t. Why not? Or is the problem that real estate agents discourage people of color from looking at neighborhoods like ours? I hope not but I don’t know. Our church (Catholic) is also very white. I chose this parish because of its attention to people with disability but again, I never thought of racial diversity. Why? And why is it that my Catholic church, which prides itself on its attention to social justice, never spoke out against the hate of the Trump campaign? The US Conference of Catholic Bishops just met a few days ago and had a great opportunity to make a statement about racism, misogyny, etc. Nothing. They did make a statement about immigrants, which is good, but what about the rest of the hate that has been unleashed? Why does my church have nothing to say about this but can’t ever let a chance to talk about abortion pass by?

At the end of Between the World and Me, Coates advises his son not to struggle for the Dreamers, for us whites. That may sound harsh, but the problem of racism is truly a white problem and we have to be the ones to see it and fix it. The burden for fixing it cannot be placed on the victims. Meanwhile, Coates observes that the Dreamers have moved on in history from plundering black bodies to plundering mother earth (fracking, pollution, etc.) and that in doing so, in putting a noose around the neck of the earth, we have put it around our own neck. Will we see any of this? As Baldwin wrote at the end of his book:

God gave Noah the rainbow sign,

No more water, the fire next time!

Will we listen to the prophets? Our track record so far isn’t encouraging.