There are good war novels, and there are bad war novels. And occasionally, a well-intentioned reader like myself gets saddled with an excruciating mess like Never Too Old to Cry.

This is a fictionalized memoir of D. G. McWilliams, a veteran of the 1st Marine Division, which fought in the Pacific Theater of the Second World War. McWilliams’ endeavor was to try to document the war from a very intimate perspective, primarily through the eyes of a small cadre of Marine recruits. Paramount among them is an idealized portrayal of himself, so thinly-veiled he may as well have mummified himself in Saran Wrap. So we have “Mack Williams” leaving his family ranch in East Texas to join the Marine Corps in early 1943. But we’re given detailed backstories on five other Marines, all of whom we follow from a first person perspective. And if that wasn’t sufficient, we become acquainted with a family of Japanese officers. And dozens more characters, however fleetingly minor, get their turn as a P.O.V. narrator. And it is here that the concept falls apart. With so many people thinking out loud, the personal stories lose coherence and the vanity of the approach is for naught.

And hell, do people think out loud. At a moment’s notice, a character will turn a simple conversation into a damn nonsensical soliloquy.

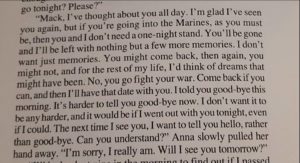

Take this gem, where our hero Mack happens to run into his freshman year crush on the day he is inducted into the Marines. She just happens to have moved to Lubbock from Crockett (clear across Texas), and just happened to be working in a store next door to the recruiting office, and just happened to be adjusting a storefront display just as Mack happened to be waiting outside.

And of course she’s gorgeous. And of course they immediately fall in love.

Outside of hackneyed war movies, people don’t talk like this. Especially eighteen-year old kids from Buttass, Texas.

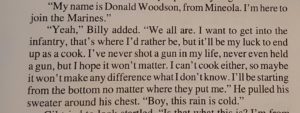

And here we have Billy introducing himself to a new fellow inductee.

I understand that these dialogues are supposed to reveal the inner workings of the minds of young men who are about to face death half a world away, but PEOPLE. DON’T. TALK. LIKE. THAT. If I had introduced myself to some other kid who was volunteering for the Marine Corps at the same time as me, and he responded with that meaningless shitstream, I would’ve immediately turned around and joined the Coast Guard.

Irritatingly, McWilliams’ concept is further diluted, because we get first person insight into everything from Japanese War Cabinet meetings to Marine regimental commanders confronting superior officers with borderline personality disorders. And we get culturally-tone deaf and outright inaccurate descriptions of Buddhist practices and Chinese prostitutes.

At times, particularly during scenes set in combat, or as the main characters bond behind the lines, McWilliams finds a voice and is able to assemble some fragments of a capable war story. But these kernels are lost amongst the chaff, and not even barely worth the effort of seeking them out.