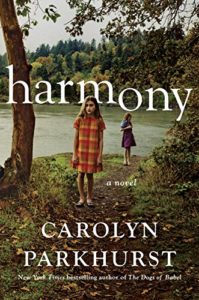

I don’t know if author Carolyn Parkhurst has a child on the autism spectrum, but if she does not, then she is an incredibly thorough researcher and empath. Her latest novel Harmony focuses on a Washington, DC, family of four who join a sort of commune in New Hampshire in order to help their 13-year-old daughter Tilly, who has an autism diagnosis. The leader of Camp Harmony, Scott Bean, is an independent educator whose approach to working with children on the spectrum and their families is very appealing to mom Alexandra and the two other families who sign on. Together their goal is to host weekly camps for families of children on the spectrum in a distraction and judgement free environment with no tech devices, no communication with the outside world, no leaving once you arrive. For Alexandra, Scott and the camp give her hope, optimism that Tilly’s difficult behaviors will become manageable. But from early on in the novel, the reader has a sense of foreboding. Through the thoughts/diaries of Alexandra and her daughters Tilly and Iris, we learn the events that brought them to the camp as well as what happens there over the course of about 6 weeks. Is this a cult? Is Scott a hero or a villain? And what do we make of Alexandra Hammond and her husband? While autism is at the center of the story, author Parkhurst gives the reader a lot to contemplate regarding family, feelings of self-worth and failure, and the power of hope.

I don’t know if author Carolyn Parkhurst has a child on the autism spectrum, but if she does not, then she is an incredibly thorough researcher and empath. Her latest novel Harmony focuses on a Washington, DC, family of four who join a sort of commune in New Hampshire in order to help their 13-year-old daughter Tilly, who has an autism diagnosis. The leader of Camp Harmony, Scott Bean, is an independent educator whose approach to working with children on the spectrum and their families is very appealing to mom Alexandra and the two other families who sign on. Together their goal is to host weekly camps for families of children on the spectrum in a distraction and judgement free environment with no tech devices, no communication with the outside world, no leaving once you arrive. For Alexandra, Scott and the camp give her hope, optimism that Tilly’s difficult behaviors will become manageable. But from early on in the novel, the reader has a sense of foreboding. Through the thoughts/diaries of Alexandra and her daughters Tilly and Iris, we learn the events that brought them to the camp as well as what happens there over the course of about 6 weeks. Is this a cult? Is Scott a hero or a villain? And what do we make of Alexandra Hammond and her husband? While autism is at the center of the story, author Parkhurst gives the reader a lot to contemplate regarding family, feelings of self-worth and failure, and the power of hope.

The structure of the novel is ingenious. Iris is writing in real time, about what’s happening at Camp Harmony in June/July of 2012. Tilly is writing from “Date and Location Unknown,” a future where her entries look back at what happened and try to make sense of it all. Alexandra’s thoughts begin at the beginning, with the birth of Tilly in 1999, and work their way up to the decision to join the camp. As we read, we gradually understand that something “cataclysmic” happened and suspense builds.

Parkhurst creates three very real and sympathetic characters in Iris, Tilly and Alexandra. I think readers will be especially drawn to 11-year-old Iris, the typically developing younger sister who seems to get dragged along for this ride without much input or understanding of what the camp is about. Through her eyes, we see an older sister who is “special,” who gets a lot of attention especially when she is acting up, and who can get violent with Iris. But through Iris we also see a fun and funny side of Tilly and also that Iris, despite all the frustrations, loves her sister and her family deeply. She wants to be the good girl, to help and do what’s right. She often sees things going on that seem odd to her but given Scott’s authority and the other adults’ deference to him, she keeps quiet. Sadly, this will lead her into situations that a child should never have to deal with. Tilly is fascinating, troubling and delightful. She has great intelligence in certain areas, such as math, but lags behind in other crucial areas such as social and emotional development. She has hit puberty and is often inappropriate (and hilarious) with her comments and questions regarding sex. Her current obsession is with monuments, and in her entries, she imagines how historians will look back on the Hammond family’s experience of the summer of 2012. Tilly’s entries are fewer in number and shorter than Iris’ or Alexandra’s, but they foreshadow the troubles to come. Tilly’s entries also reveal that she has seen and understood more than we might have given her credit for. Iris frequently mentions that Tilly is often listening and picking up information when you think she is distracted with something else. One entry of Tilly’s that really resonated with me has to do with future elders talking around the campfire about the “Great Autism Panic” of the 21st century, when, “Parents seemed to be afraid of their children’s brains.” Tilly has connected a lot of the dots that led the family to Camp Harmony.

Alexandra has a special place in my heart because, as an autism parent, I feel like I know her, I could be her, I have been her. I know a lot of Alexandras thanks to the wonderful world of autism. It’s easy to judge another parent for his/her decision making, but through her entries, you get a chance to walk a mile in Alexandra’s shoes and maybe understand why some parents do what they do. They aren’t crazy, they aren’t trying to take the easy way out. I love the journey that Parkhurst describes through Alexandra because it is a real autism-parent journey. Alexandra talks honestly about Tilly’s behaviors, about trying to learn everything about autism, finding the right school placement (this part is done exceptionally well), the stress on marriage, the stress of finances. But this is not a “woe-is-me” “poor autism parent” narrative. It is an honest explanation of what a parent experiences when your beautiful exceptional child does not fit in any of the programs out there, when behaviors get beyond your ability to cope and lead to genuine danger. Alexandra beats herself up a lot. This one got to me:

Some days you’re an idiot, and some days you’re a fucking idiot. It’s the winter of 2008, and you’ve developed a habit of berating yourself while you drive.

And:

Were you ever a good person? Some part of you knows that you were, maybe even are. But the bad stuff is so much more prominent.

Funny enough, Alexandra develops her own obsessions to cope, including video games that allow you to build a perfect civilization, where you can protect inhabitants and get rewards. It’s purely by chance that she learns of Scott Bean, and it takes a few years before she really investigates who he is and what he can offer. Later both Alexandra and Tilly will look back and imagine “what if” things had gone another way.

While the book is suspenseful and something sinister is on the horizon, I will tell you that the ending is ultimately hopeful and optimistic, just like Alexandra and the other parents she works with at Camp Harmony. If there is one thing I’ve learned from having special needs kids, it’s that things can always be worse and you have to keep picking yourself back up and getting to the job at hand. As Alexandra writes:

Happiness in the real world is mostly just resilience and a willingness to arch oneself toward optimism.

We gravitate toward those who can help us on that journey. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. Can you blame us for trying?