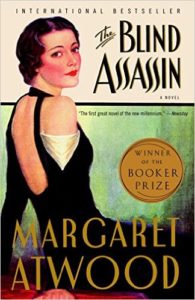

The Blind Assassin is Margaret Atwood’s Booker Prize and Dashiell Hammet Award winning novel (2000) that spans the major events of the 20th century while telling the tragic story of the Chase sisters. It is an ingenious combination of history and mystery with love, infidelity, avarice, godliness, war and literary references woven deftly within. This is also a novel about women, class and perception, or misperception/blindness as the case may be.

The Blind Assassin is Margaret Atwood’s Booker Prize and Dashiell Hammet Award winning novel (2000) that spans the major events of the 20th century while telling the tragic story of the Chase sisters. It is an ingenious combination of history and mystery with love, infidelity, avarice, godliness, war and literary references woven deftly within. This is also a novel about women, class and perception, or misperception/blindness as the case may be.

The novel is narrated by Iris Chase Griffen, daughter and wife of captains of industry. She is the last of the Chases and Griffens except for a granddaughter whom she has never met. In 1999, Iris is elderly and is writing down the story of her life and her sister Laura’s for her granddaughter, for reasons she will explain beautifully at the end. Atwood is a superb storyteller and The Blind Assassin draws in the reader irresistibly from its first lines.

Ten days after the war ended, my sister Laura drove a car off a bridge.

Iris goes on to write that witnesses confirmed it was intentional, a suicide, but family money and the police ensured that it was categorized as a tragic accident.

It wasn’t the brakes, I thought. She had her reasons. Not that they were ever the same as anybody else’s reasons. She was completely ruthless in that way.

How could a reader not be drawn in? Why did Laura kill herself? What does the war have to do with it? Why does Iris call her sister ruthless? Over the course of 500+ pages, Atwood unravels the fascinating yet tragic tale, and within this novel, Atwood creates another story, also called “The Blind Assassin.” This is the sci-fi novel written by Laura Chase and published after her death, a novel that has gained a cult following over the decades since its publication. As Iris relates the history of her family — the successful factories, marriage, the horrors of WWI for her father, her mother’s early death, depression, strikes and economic ruin — the reader also gets chapters from Laura’s book. This story involves a world with warring nations, slavery, subjugation of women, and an oppressive religion that calls for human (female) sacrifice. “The Blind Assassin” also happens to be narrated by a contemporary couple who seem to be having an illicit love affair.

As noted above, Atwood’s novel revolves around the idea of perception and figurative blindness. Through Iris, who seems to be very honest about herself and her past, we readers think we see the truth, but as Iris reveals her own blindness, we see that perhaps we, too, have been misperceiving events. Atwood is not being a trickster here; rather she is putting us in the position of her characters. If anything, this revelation of truth humanizes her characters rather than making readers feel duped. Iris and Laura, the central characters, come from wealth, but they live in a small town rather than the social center (Toronto); they are not particularly connected to their local community as they have been tutored (poorly) at home rather than attend the local school. Their father is struggling psychologically and emotionally since WWI, and the death of his wife is hard for him and his daughters, whose true parental figure is the cook Reenie. Much responsibility is placed on Iris to look after and take care of Laura, who is “different”; Laura seems to be a dreamy child, obsessed with God and earnest about doing service on behalf of the poor (like her mother). Iris seems to be the practical and pragmatic child, and yet there is much she doesn’t understand or see, while Laura, the strange and sensitive child, sometimes sees reality a little better than Iris. In one telling exchange, Iris tells Laura, who disapproves of Iris’s engagement, “I’ve got my eyes open,” to which Laura replies, “Like a sleepwalker.” Both Laura and Iris are frustrated with their lives. On the surface, they seem beautiful young women with everything you could possibly want, but perception is not reality. Iris, who admits to being attracted to nice clothes and a comfortable life, is nonetheless stuck in a horrible marriage (with a truly bitchy sister-in-law), and she is a fish out of water in Toronto society. Laura longs for something outside the norm; she wants a “real” life among regular people, helping the poor and hard luck cases. Neither sister has the power to get what she wants without making terrible sacrifices.

Certainly, one could choose from a number of themes in the novel to note in a review — war and injustice, the class struggle, politics and economics. I was especially impressed with Atwood’s use of classic literary works in this novel. Iris’ explanation of Coleridge’s Xanadu and Laura’s translation and understanding of Dido’s death in the Aeneid are used to brilliant effect and complement the plot beautifully. But I will end with the theme that stayed with me at the end — writing and remembrance. Throughout the novel, Iris refers to and visits the family graves in the local cemetery, graves overseen by a large statue of two angels. Atwood makes frequent references to remembrances, the need to be remembered, the significance of how one is remembered. Given that this is a novel that contains a novel, and that our narrator is involved in the conscious act of writing, The Blind Assassin also has something to say about writers, monuments to them/their work, and the writer’s desire to put form to memories. Iris is mildly irritated by the pilgrims who visit the family tomb with flowers for Laura and the academics who contact her for interviews (denied); she is much more interested in the graffiti on the bathroom wall at the donut shop. But Iris understands the importance of what she leaves behind, that she has some control over what is remembered and who has access to that memory. In her final entry to her diary, Iris writes what I suspect any writer must feel upon completion of her work:

… I leave myself in your hands. What choice do I have? By the time you read this last page, that — if anywhere — is the only place I will be.

Writing and creating is sort of an act of faith; one never knows who will read it or what they will make of it. But writing is a way to say your piece as well, and what you write can have resounding impact beyond your own world. Writing is an empowering act for those whose voices have been silenced or simply unheard in life. Margaret Atwood is an incredibly powerful writer and I imagine her voice will live on for generations to come.