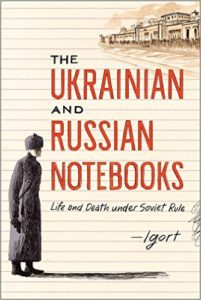

At the beginning of CBR8, I reviewed two graphic novels that deal with contemporary history: Marzi, about Poland under martial law and the Solidarity movement, and War Brothers about civil war and child soldiers in Uganda. Both were excellent and demonstrated for me that the graphic novel is a great way to introduce readers to events that might have either passed notice or seemed too far away to really matter. In particular, I think the graphic novel lends itself to drawing in young readers, educating them about serious events in history and perhaps even luring them into reading more on such topics. The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks by Igort is another example of a graphic novel tackling a very serious subject, Russian/Soviet oppression, and making it accessible to readers who have little to no familiarity with the topic.

At the beginning of CBR8, I reviewed two graphic novels that deal with contemporary history: Marzi, about Poland under martial law and the Solidarity movement, and War Brothers about civil war and child soldiers in Uganda. Both were excellent and demonstrated for me that the graphic novel is a great way to introduce readers to events that might have either passed notice or seemed too far away to really matter. In particular, I think the graphic novel lends itself to drawing in young readers, educating them about serious events in history and perhaps even luring them into reading more on such topics. The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks by Igort is another example of a graphic novel tackling a very serious subject, Russian/Soviet oppression, and making it accessible to readers who have little to no familiarity with the topic.

In 2008 and 2009, Italian graphic novelist Igort traveled throughout Ukraine and Russia collecting stories of oppression under Soviet rule. The Ukrainian Notebook focuses on the famine of the early 1930s, while the Russian Notebook revolves around the work and 2006 assassination of Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya. Igort’s work is powerful; he speaks with eyewitnesses to the events he describes, family members and friends, and sometimes even consults government documents. The shocking truths that Igort has written about are accompanied by brutal graphic images, often in black and white, always in drab colors, sometimes featuring splashes of red. The reader can sense Igort’s horror at the history his subjects reveal, and also his anger and frustration that history repeats itself. His goal is to draw our attention to the atrocities and injustices that continue in Russia and Ukraine and celebrate the bravery of those who have tried to stand up to and expose government oppression.

In 2008, Igort travelled to Ukraine and interviewed a number of elderly residents who were born in the 1920s and experienced childhood during the turbulent and dangerous time of collectivization, “dekulakization” i.e., the rounding up and deportation of “rich peasants,” and the holodomor, i.e., the famine and starvation of the countryside. Ukraine has traditionally been viewed as the breadbasket of Russia/USSR, although anyone familiar with Russian history knows that early 20th century peasant farming was a precarious affair. Agricultural methods hadn’t changed dramatically since the time of serfdom and thus were rather inefficient. When Stalin rose to power at the end of the 1920s, his economic plans included the “rapid industrialization” of the Soviet Union, which required that mass surpluses of food (which did not exist) be taken to cities to feed workers and be exported for cash. This plan also called for the “collectivization” of agriculture, meaning that the small existing farms would be consolidated into large industrial farms. As you can imagine, Soviet authorities did not approach this plan in a gentle or gradual manner. Peasants were uprooted and stripped of their land. Unrealistic “five-year-plans” were imposed on these new collective farms, and failure to fulfill plans was considered a crime. Naturally, plans were not met, and to explain this failure to the public, Stalin and his government blamed spies, saboteurs and “kulaks,” i.e., “rich peasants.” Rich peasant is an oxymoron, btw. A campaign to round up these criminals (de-kulakization) led to arrest, deportation to Siberia and frequently deaths of innocent people. The people of Ukraine experienced harsh poverty and widespread starvation, with countless dying as a result of Stalin’s policies. Some of what I have described here is alluded to in Igort’s book. If I have a criticism, it is that he really doesn’t provide the background to the horrors that followed, and it might help the reader to understand a bit better what collectivization, kulaks, etc. were. I have a PhD in Russian/Soviet history, so I can’t help myself when it comes to this stuff. At any rate, Igort provides shocking and horrific stories from the time of starvation. His subjects’ memories of these times are hard to read but should be told. They recall going into the woods to find roots to eat, going without food for long periods of time, having no meat or milk, often no bread, suffering from weakness and illness without medical support of any kind. They remember dead bodies and the very real threat of cannibalism. In recent years, Ukraine has campaigned for the UN to recognize the starvation, the holodomor, as genocide, but given Russia’s veto power, this will never happen. Some countries, including the US, have acknowledged the famine as a crime against humanity.

The Ukrainian Notebook also examines some contemporary issues in Ukraine as well, such as radiation poisoning, poor health care, and the shabby treatment of the elderly. A postscript to this dual volume addresses the current war with Russia in Ukraine.

The Russian Notebook, the second part of this collection, is the better of the two notebooks, in my opinion, because it deals with the life and work of a contemporary individual instead of a phenomenon that covered a vast geography and time. In relating the events surrounding the work and death of Anna Politkovskaya, Igort can provide a lot of detail and evidence of Russian corruption. He has her words from her investigative reporting in Novaya Gazeta, interviews with people who knew her, and transcripts from trials that she covered. Anna Politkovskaya made a name for herself and drew the ire of authorities for her reporting on the Russian war in Chechnya. She interviewed soldiers and travelled to Grozny to interview those who had been unjustly rounded up and tortured; she met with family members whose loved ones, generally males age 14 and older, were rounded up and never heard from again. In interviewing Anna’s friends, such as her translator in France, Igort uncovers Anna’s noble character and selflessness. She was a person of great integrity and honor, pursuing the truth even when it was clear that authorities were following her and attempting to intimidate and harm her. The stories that Igort tells from her investigative work in Chechnya are detailed and horrifying. The Red Army engaged in systematic abuse and torture of the locals, which not only radicalized Chechens but also led to something called the “Chechen syndrome” among soldiers; having been put in a position where they were expected to torture and kill without provocation, they reverted to violence even after they had returned home.

In 2006, after having reported on Chechnya and Russian atrocities for several years, Anna was shot and killed in the elevator of her apartment building in Moscow. Several friends of hers, also reporters for Novaya Gazeta who continued her work, were subsequently gunned down as well. While I am sure her assassination was covered in the Western press, I don’t think most people understood the importance of Anna’s work or why she was a threat. As Igort writes,

…the system depends on a cloak of indifference that can cover up any kind of crime without any punishment….

Indifference is dangerous, and that is a lesson everyone needs to understand, no matter where in the world you live. Igort provides this quote from Anna that sums it up well:

I see that people would like to change their lives for the better but can’t make it happen. To keep going, they start lying to themselves. To my way of thinking, this is like being a mushroom that hides by growing under a leaf. Almost certainly someone is going to find it, pick it, and eat it.

That’s why, if you are born a human being, you shouldn’t act like a mushroom.

I would recommend The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks to anyone who would like to familiarize themselves just a bit with modern Russian history as it pertains to their treatment of non-Russian peoples. I hope it would entice young people, such as middle and high schoolers, to read more about Russian and Soviet history, Ukraine, Chechnya, and the other parts of the world that have at one time or another been under Russian control.