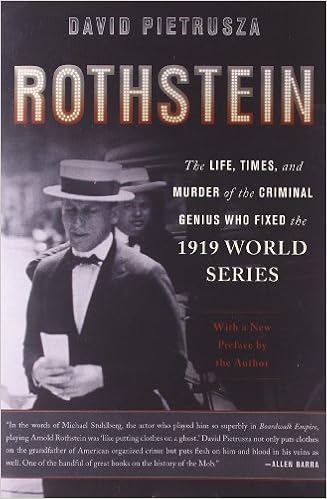

If you’re not familiar with the name Arnold Rothstein, you might be aware of the fictional portrayals which have outlived him. F. Scott Fitzgerald introduced him into The Great Gatsby as Meyer Wolfsheim, the carnivorous gambler who unnerves Nick Carraway. Damon Runyon, on the other hand, humanized Rothstein as the put-upon man about town Nathan Detroit in the stories that would eventually become Guys and Dolls. As those wildly divergent interpretations might lead you to guess, Rothstein was a slippery persona, hard to know and even harder to befriend. Neither Fitzgerald nor Runyon had a solid grasp on the man, according to his biographer, David Pietrusza.

So who was Arnold Rothstein? Well, he was a tremendously powerful and influential man for a few decades near the beginning of the 20th century. His prowess as a gambler provided him enough wealth to become known as The Big Bankroll. While he was an unusually sharp and clever man for his social set, the real trick was to make a bet as risk-free as possible. A. R. was extraordinary at rigging the odds in his favor as much as possible. He hated losing and didn’t share the normal gambler’s love of risk. He realized early on that there was more money to be made in facilitating others in their need to gamble, so he operated casino games in his clubs and created the “floating crap games” that would become so associated with Nathan Detroit.

Rothstein used his bankroll to become something of a master middleman. Criminals who needed a loan to get their nefarious enterprise off the ground could turn to Rothstein, provided they were willing to pay his extraordinary interest rates. Men in trouble could count on him to wield the judges and Tammany Hall officials in his pocket, as long as they cut him in on their next big deal.

Pietrusza goes into a staggering, dizzying amount of detail on many of these deals, throwing around dozens of names (most of them colorful and/or legendary: Waxey Gordon, Legs Diamond, Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky) and massive sums of money with relative ease. Pietrusza has really done his homework, and has unraveled some mysteries that have stumped scholars of organized crime for decades.

Of course the biggest swindle of Rothstein’s career is the 1919 World Series, the fix that would secure his place in the history of infamy. The extent to which Rothstein masterminded the scheme or merely served as the go-between remains in dispute, but it cements his legacy to consider that a crime this large could not have been contemplated without his involvement. Of course, the fix was undermined by the incompetence of some of A.R.’s associates, whose massive betting and loose lips caused suspicion of a fix to become widespread even as the series was being played. It didn’t help that some of the crooked players involved weren’t capable of throwing the games without making it obvious.

Ultimately the point of the story of the 1919 World Series isn’t Rothstein’s brilliance, nerve, or wealth. It’s that he’s the one who got away with it. The players, who never saw nearly as much money as they’d been promised, were banned from baseball for life. The small-time gamblers who got caught up in the plan wound up in jail or in exile. A. R. had to face some impertinent questions in front of a grand jury, but the law either couldn’t or wouldn’t get its hands on The Big Bankroll.

There are other schemes of course, including the illegal import of high-quality whiskey and the start of the international drug trade. There are times when Pietrusza’s book reads less like the biography of one man than a history of New York in the 1910s and ’20s, with the author going into detailed accounts of notable crimes, corrupt police commissioners and district attorneys, and society types like Fanny Brice.

There are a lot of deaths too of course, including eventually Arnold Rothstein’s. Shot in the gut in a hotel room by a man he had stiffed on a gambling debt, A.R. died in early November 1928, just days before he would have collected over a million dollars in winnings from betting on the outcomes on Election Day. His death caused his financial empire to collapse and seemed to herald the end of the swinging 1920s.

As a coda to the book, Pietrusza follows up with the fates of every criminal, politician and socialite mentioned in the text. Overall these snippets give a comprehensive overview of the history of American crime in the first half of the 20th century. And all of them, in one way or another, were connected by Arnold Rothstein.