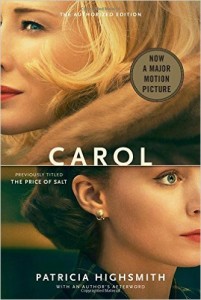

Well, it’s not like Cate Blanchett would choose to star in the adaptation of a bad Patricia Highsmith novel. I haven’t actually seen the film, but the trailers and still photographs project a certain sort of aesthetic that I found intriguing–rich colours, gleaming cocktails, and soft lights; crisp coral lipstick on a smile that says come hither and f**k off. This is the first novel of Highsmith’s that I’ve read; as Val McDermid points out on the cover of my edition, it has “the drive of a thriller but the imagery of a romance.”

Well, it’s not like Cate Blanchett would choose to star in the adaptation of a bad Patricia Highsmith novel. I haven’t actually seen the film, but the trailers and still photographs project a certain sort of aesthetic that I found intriguing–rich colours, gleaming cocktails, and soft lights; crisp coral lipstick on a smile that says come hither and f**k off. This is the first novel of Highsmith’s that I’ve read; as Val McDermid points out on the cover of my edition, it has “the drive of a thriller but the imagery of a romance.”

It’s the 1950s in New York; anything apart from heterosexual monogamy is viewed with disgust by the eyes of the law and most people–particularly soon-to-be-divorced businessmen trying to get sole custody of their child, and by young wannabe artists whose egos are bruised because their girlfriends don’t want to settle down with them. Therese is about twenty, dating Richard in a desultory sort of fashion, and an aspiring stage-set designer (in the film, I believe she’s a photographer–the same point about how she views life at a remove works for both) who is working long hours in the toy section of a large department store. One day she meets Carol, about to be divorced from Harge, who is buying the daughter she might lose a doll. Therese knows that Carol is right–she sends Carol a personal card with the toy delivery, and their lives are locked together.

Highsmith does a brilliant job of showing how Therese’s work and life before Carol veers between the grotesque and the boring, infusing tiny details with horror; at the workplace cafeteria, for example: “The woman made a tremulous, dismissing gesture. She pulled her saucer of canned sliced peaches towards her. The peaches, like slimy little orange fishes, slithered over the edge of the spoon each time the spoon lifted, all except one which the woman would eat”(7-8). In contrast, Carol is smooth and cool, tinged with melancholy and passion. Their affair unfolds at a glacial pace; again, the tension is built in a way that suggests a thriller rather than a romance. It’s shadowed by the cigarette smoke, potentially mixed motivations, and paranoia of noir–there’s even a private detective and a Gothic moment involving a portrait. Despite the ellipses and elusiveness of Therese’s and Carol’s connection, the novel is also infused with pure romantic yearning, the sense that Therese and Carol belong together, that their desires are utterly right for them, and that any other life or person is simply wrong. This certainty brings them both misery and joy; part of the mastery of this novel is how Highsmith plays with expectations–we know how things are supposed to turn out, but it’s at times terribly uncertain whether they will do so.

Title taken from Marilyn Hacker’s “Sonnet on a Line from Venus Khoury-Ghata”.