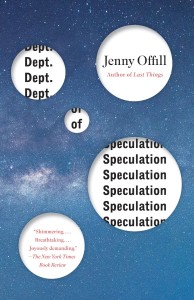

This novel is short and told in what I might call an impressionist manner, its form occasionally reminiscent of entries that you could find in Twitter or FaceBook updates. And yet in the end, it is a very rich story of a marriage and motherhood, with poetry, philosophy and some wry commentary on both institutions along the way.

This novel is short and told in what I might call an impressionist manner, its form occasionally reminiscent of entries that you could find in Twitter or FaceBook updates. And yet in the end, it is a very rich story of a marriage and motherhood, with poetry, philosophy and some wry commentary on both institutions along the way.

The narrator, who refers to herself as “the wife,” takes us through the highlights and lowlights of her adult life: dating, yoga, work, colic, bedbugs, infidelity, and her own growing depression. She is introspective and recognizes some of her own limitations. For example, she sees a “crookedness” in her heart that loving her husband and child hasn’t fixed. She notes,

Three things no one has ever said about me:

You make it look so easy.

You are very mysterious.

You need to take yourself more seriously.

She views home as a way of keeping the people you want in and everyone else out. I never liked to hear the doorbell ring. None of the people I liked ever turned up that way.

The wife has published a book and struggles to write her second. Meanwhile, she teaches writing at a college and also takes on work as a fact checker and then as a ghost writer. Frustrated or disappointed expectations, life not turning out the way one planned, seems to be a recurring theme. The wife wanted to be an “art monster,” to write, never to marry, and yet she has married, writes for others and is not producing her own art. There is a palpable sadness to Offill’s writing, a sadness that I think many women share with the wife — having a colicky baby, being annoyed by and terrified for the baby, putting aside one’s own work, not feeling a part of the pack of yoga/school moms. The wife demonstrates great snarky humor in relating some of these things.

And that phrase — ‘sleeping like a baby.’ Some blonde said it blithely on the subway the other day. I wanted to lie down next to her and scream for five hours in her ear.

She speaks very much like I or my friends would, but it’s harder to be humorous about depression and the strains on a marriage. The wife might come across as a rather hard woman to know and become close to, but I think she is one of the most realistic women I’ve encountered in fiction. I found myself having an enormous amount of empathy for her.

I think when we read novels, we hope to find solutions, that somehow the plucky heroine is going to find a way to make everything work or find something strong in herself to persevere and be transformed. But for lots of people, life’s problems are just a bitch and you muddle through as best you can. Many of the quotes that the wife relies on have to do with life just being hard and unsatisfactory. The quotes from Buddhists really bring that message home. The wife is also a fan of Rilke, and this quote seems to embody her philosophy:

Surely all art is the result of one’s having been in danger, of having gone through an experience all the way to the end, to where no one can go any further.

Life is about getting through it — whether it’s bedbugs and head lice or depression and a troubled marriage. It can be traumatic and ugly, and there’s no promise of a sublime happiness for having endured the difficult times. But that doesn’t mean that life completely sucks and isn’t worthwhile either. As much as I hate the expression, “It is what it is” seems to fit here.