In every cultural movement, you’ll have the people who are the face of the scene and then you’ll have the background players. Bobbie Brown, best known as the girl in the Cherry Pie video, launched a thousand boners in 1990 writhing around beside Warrant in short shorts, windswept and getting soaked with a fire hose. I remember thinking it was so sweet and right that she married Jani Lane: the front man gets the hottest girl and they make beautiful music together forever.

Of course, that’s not what happened.

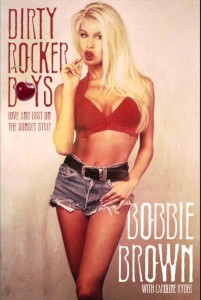

In her 2013 memoir, Dirty Rocker Boys, Brown consciously uncouples the relationship between rockers and their chicks , their groupies, their fans, and their video vixens. Brown, who is originally from Louisiana, made it big in the cock rock scene of Los Angles in the early 90’s. She was “discovered” like countless other pretty girls before her and allowed to be the most attractive accessory in a music moment that set off an epidemic of pearl clutching America as MTV saturated suburban airwaves with sex and booze obsessed flamboyant rockers.

If you grew up in this era, you are probably feeling nostalgic right now. I had great fun re-watching all the videos referenced in Brown’s book. I shouted the lyrics and giggled at the cartoonish sexuality and cavorting. And there is no shortage of books written by the bands themselves or music journalists close to them. So why read Brown’s book?

Everyone who is the face of the scene has a lot at stake when telling their chapter of the Sleaze Metal Olympics. Bands want to burnish their legacy and journalists want to showcase their access. No one wants to jeopardize future sales with controversy or a complicated narrative so everyone sticks to the plot: sex, drugs and rock and roll.

Brown gives us “subversive knowledge”. That is, the knowledge that is gleaned from people in subordinate positions, which is often much more nuanced than the people who hold the power. The extremely masculine environment of the male rock performer doesn’t have room for anything but the character you portray. It was the women who saw the Rock Gods when they had human moments: the heartbreak, the addiction, the doubt and anxiety.

Brown will tell you about Sebastian Bach’s coke boogers, Dave Navarro’s technique of shooting smack with a toaster, and yes, Tommy Lee’s “swimsuit area”. There is lots of dish. But there are also darker tales that humanize all the people involved.

Brown’s writing is direct and empathetic and cuts through the indulgent pageantry of all the iconic concerts and videos. She has lived everything she’s written about and has no agenda with this book. People like Brown, who write memoirs, are often derided as peripheral players who contribute nothing but want to cash in with a tell-all. That is missing the point.

The point is, women like Brown, provide an alternative narrative to the public perception. They aren’t the face of the scene, they are what they were allowed to be. But being objectified doesn’t remove Brown’s capacity for observation or insight. People often behave the freest around those they perceive as subordinate or temporary. In the disposable role of video vixen or rock wife Brown permeated the entire scene. She’s not just giving a voice to the women on whose breasts and butts were built a Hair Metal Empire, she’s giving depth to the two-dimensional tropes of the preening rocker and bouncy babe. Brown might have been in the background, but she was still a major player.

Would you rather have your best friend or your ex write your biography? Sure. But which would you rather read?