This is the eighth of my 10 African books this year, and the first by a Malawian author–I couldn’t well leave Malawi off the list since moving here was what inspired me to read more African books in the first place!

This is the eighth of my 10 African books this year, and the first by a Malawian author–I couldn’t well leave Malawi off the list since moving here was what inspired me to read more African books in the first place!

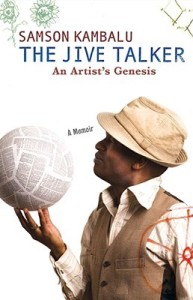

Samson Kambalu was born in in 1975 into a Christian family of eight, and spent most of his childhood moving among remote villages in Malawi. Kambalu tells his story in chronological anecdotes, mostly, including early memories of being plagued by parasites, poverty, malaria, jiggers and other hazards of a rural African childhood, complemented by phases of obsession with Michael Jackson, Footloose, Nietzsche, girls, fashion, and sports. He veers into descriptions of various religious sects he comes in contact with, including a phase of being Born Again, closely followed by forming his own life-affirming religion at age 12, Holyballism. The Jive Talker of the title is Samson’s father, a man we gradually learn has a dangerous relationship with alcohol, who quotes Nietzsche and provides his family with starvation wages as a medical assistant who travels from rural post to rural post in Malawi with his family of 8. The second half of the book covers Samson’s schooling at Kamuzu Academy, subsidized by then-dictator/president Kamuzu Banda and modeled on the best British public school system.

I really enjoyed the descriptions of growing up in Malawi. If you’ve read The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, you’ll recognize the style: anecdotes set in sub-Saharan poverty, but told with such verve and childish optimism that you can’t help but be charmed. Each section is divided up by region of the country where the family lived, following Samson’s father’s job, and that was entertaining for someone living here–I’ve been to most of the places, either on weekends or on work trips, so the descriptions resonated and added another flavor to my (super-expat) understanding of life in Malawi.

I also enjoyed the kids’ (even though told by a grown up) perspective of African and Malawian politics–something that is hard to come by since African (in general) politics are so dramatic and therefore color so many discussions.

In short: it was nice to see Malawi, a small and oft-forgotten, but truly lovely, place written about so lovingly for a wider audience.

That said, this book is certainly not a page turner. It took me a long time to read. Because of it’s memoir format, it reads almost like a journal, and although there’s a story arc, there’s not much momentum. Part of that, I’m sure, is the nature of describing a childhood in Malawi–the things that make Malawian anecdotes charming don’t lend themselves to narrative speed. Malawi itself is kind of a slow-moving place, so it is fitting that a Malawian memoir would be a little meandering. Fair enough! But I put this book down often and picked it up only when I was done with more energetic books and wanted a palate cleanser. There are also, sometimes, whole pages written in list form, which could easily have been scrapped.

Rating: 3/5. Solid points for charm and anecdotal storytelling that helps us mzungus understand the warm heart of Africa a little better. Minus points for lack of page-turn-ability. I’ll definitely recommend this to anyone traveling in this part of the world, or moving to Malawi.