This graphic novel by Alison Bechdel, perhaps knowns to some as the creator of the Bechdel test, to others as the creator of the comic Dykes to Watch Out For, has won critical acclaim and is currently featured as The Atlantic’s 1book140 selection for LGBTQ month. I found to to be a truly engaging read both for its art and for its written content.

This graphic novel by Alison Bechdel, perhaps knowns to some as the creator of the Bechdel test, to others as the creator of the comic Dykes to Watch Out For, has won critical acclaim and is currently featured as The Atlantic’s 1book140 selection for LGBTQ month. I found to to be a truly engaging read both for its art and for its written content.

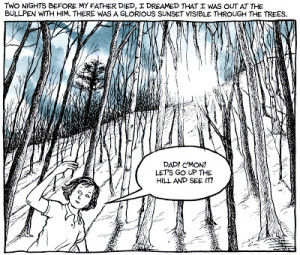

The art is done in black, white and blue tones. Bechdel mixes up her own comic illustrations of her family with detailed renderings of the family home and its decor, maps of her town (and the village from The Wind in the Willows), handwritten notes, and a few “portraits.” Some of my favorite images were Bechdel’s drawings of the Pennsylvania landscape, including a series of beautiful drawings with descriptions of environmental devastation.

…the sparkling creek that coursed down from the plateau and through town was crystal clear precisely because it was polluted. Mine run-off had left the water too acidic to support life of any kind. Wading in this fishless creek and swooning at the salmon sky, I learned firsthand that most elemental of all ironies. That, as Wallace Stevens put it in mom’s favorite poem, ‘Death is the mother of all beauty.'”

Much like that description of the environment, the story of Fun Home is about the sad and dysfunctional Bechdel family, which produced creative genius in a stagnant and poisonous environment. Shortly before her father’s untimely death at age 44, Alison had come out as a lesbian and her mother revealed that her father was also gay and had had affairs with men and boys. “Fun Home” was the name Bechdel family gave to their home, a funeral home, in a remote part of Pennsylvania. The Bechdel family had had the business for generations, and her parents took it over when Alison was just a baby in addition to holding teaching jobs at the local high school. In relating her family history, particularly her relationship with her father and her journey toward discovery of her (and his) sexuality, Bechdel incorporates the literature that was so important to her parents and to her. References to F. Scott Fitzgerald, Proust, James Joyce and Henry James give a depth to the narrative that is somewhat surprising for a graphic novel. Fun Home provides some rather neat synopses of Ulysses and Remembrance of Things Past, for example, while linking those stories to the odyssey of her childhood and the relationship she had with her father.

I employ the allusions to James and Fitzgerald not only as descriptive devices, but because my parents are most real to me in fictional terms.

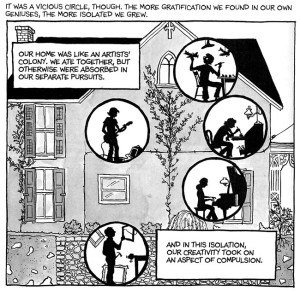

Neither of her parents were particularly warm people, certainly not to each other but not even in relation to their own children. Her father spent his free time reading and working on rehabbing the house as well as the outside grounds. Her mother was working on an advanced degree and was involved in local theater as well as playing the piano. Bechdel notes that every member of the family retreated into their own personal interests.

It’s childish, perhaps, to grudge them the sustenance of their creative solitude. But it was all that sustained them, and was thus all-consuming. From their example, I learned quickly to feed myself. It was a vicious circle, though. The more gratification we found in our own geniuses, the more isolated we grew. … in this isolation, our creativity took on an aspect of compulsion.

By age ten, Bechdel had a full blown case of OCD, which is heartbreaking to read. By the time she was in high school, and enrolled in her father’s literature course, she and her father had learned to speak to each other through novels. But this did not lead to a warm and open relationship even when Alison came out and discovered the truth about her father’s sexuality. She believes his death was a suicide and not an accident, but her proof isn’t terribly convincing. Nonethless, Bechdel’s words and images convey the genesis and progression of her father’s troubled life and relationships with great care and profound thought.