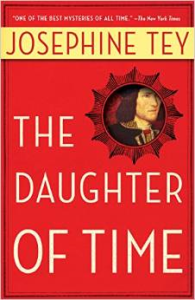

The Daughter of Time (1951) is the first novel by Josephine Tey that I’ve read, and it’s a rather unconventional  mystery, so I have no idea how the style relates to any of her other detective fiction. Based around the aphorism that “Truth is the daughter of time, not authority” (Sir Francis Bacon), the novel, via Scotland Yard Detective Alan Grant, investigates whether Richard the Third really murdered his nephews in the tower. Grant is laid up in hospital and bored; a friend brings him an array of photographs and portraits on which to practice his physiognomic skills. He comes across Richard III, and is startled that he seems more saint than cold-blooded killer–this makes him decide to prove the king’s innocence. Instead of dashing down streets or staking out abandoned warehouses, the hot pursuit in this novel is through books. He’s aided by a likeable young American scholar, Brent Carradine, and the various friends and nurses who visit him.

mystery, so I have no idea how the style relates to any of her other detective fiction. Based around the aphorism that “Truth is the daughter of time, not authority” (Sir Francis Bacon), the novel, via Scotland Yard Detective Alan Grant, investigates whether Richard the Third really murdered his nephews in the tower. Grant is laid up in hospital and bored; a friend brings him an array of photographs and portraits on which to practice his physiognomic skills. He comes across Richard III, and is startled that he seems more saint than cold-blooded killer–this makes him decide to prove the king’s innocence. Instead of dashing down streets or staking out abandoned warehouses, the hot pursuit in this novel is through books. He’s aided by a likeable young American scholar, Brent Carradine, and the various friends and nurses who visit him.

It’s an odd sort of detective novel–sort of like Rear Window but with more butts of malmsey and treason. It’s amusing seeing the man of action with too much time on his hands sinking his teeth into this centuries-old mystery, and the musing on how lies become myth become history is very interesting–there’s a contemplative, philosophical side to the novel that’s very refreshing. It moves exactly as slowly as it needs to, and the dramatic moments emerge naturally. It’s also odd to read because writers like Philippa Gregory have attempted to rescuscitate the character and nobility of the hapless king in the last few years, but although Grant begins the investigation on an impulse, the actual process of deduction is based on logic, considering alternative suspects, and interrogating theories and biased witnesses, which gives the text far more heft than the emotional resonance employed by some romantic historical fiction writers.