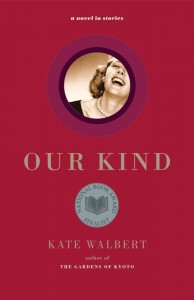

This short novel, a finalist for the 2004 National Book Award, deals with a circle of women who married and had children in the ’50s somewhere in New England. Much of their story is told in flashbacks from a point in the 1990s, when they have aged and have lost many of those who had been close. As a result, we get nothing like a linear narrative, and that’s not terribly important. The relationships that these women form, the choices they have made, and how those two things influence their lives are the story. While the novel can be humorous, there is an underlying melancholy that stayed with me after I’d finished.

This short novel, a finalist for the 2004 National Book Award, deals with a circle of women who married and had children in the ’50s somewhere in New England. Much of their story is told in flashbacks from a point in the 1990s, when they have aged and have lost many of those who had been close. As a result, we get nothing like a linear narrative, and that’s not terribly important. The relationships that these women form, the choices they have made, and how those two things influence their lives are the story. While the novel can be humorous, there is an underlying melancholy that stayed with me after I’d finished.

The structure and voice of this work stood out immediately as they are rather unconventional. The narrator seems to be a member of the group or perhaps the collective consciousness of the group. As mentioned above, the structure of the novel is not linear. Walbert dips into the past, moving back and forth with the present, in each chapter. One of the amusing sections of the story involves a book club that Viv runs at the hospice, where their friend Judy resides. The selection of the month is Mrs. Dalloway, which deals with time passing and the empty life of its protagonist. I reviewed this novel earlier in the year and noted that its delivery is sort of stream of consciousness, not a strict linear progression. Mrs. Dalloway is one of Viv’s favorite novels, but Mrs. Lowell complains that it’s confusing and she couldn’t make heads or tails of it. She’d much rather read Dickens or Austen. When Viv tries to redirect the conversation to the character Clarissa Dalloway and whether or not Woolf had, in fact, described them — this circle of women– the conversation turns into how pretty the name Clarissa is and what names the women would have liked to have given their children. The fluidity of time throughout Our Kind shows how little the women have changed in their attitudes and values since girlhood. They’ve built their defensive walls and maintain them so that they can get through life.

The women featured in this work seem to be a rather affluent lot, although not all came from money. In some ways, I suppose, they could stand in for their generation. The expectations for women post WWII were quite limited: to marry and raise children, even if this was not what they particularly wanted or were suited for. The fictional women of this story have had to deal with pain and loss. Most of them have been through divorce, and each takes a turn telling the others about “the beginning of the end,” i.e., the point at which they now see their marriages took a turn for the worse. Others have had to deal with alcoholism, grave illness, death. The stories of Esther and Viv stuck out for me. Esther was an artist married happily to another artist; she never had children but was deeply in love with her husband — the only one of the group who seems to have had that experience; thus, the loss of her husband was a devastating blow for Esther. Viv gave up an opportunity to pursue her studies in order to marry; when she tried later in life to pick up where she left off, it was too late. For her, the choice to marry was the beginning of her end — the end of her independence and self-identity. Esther and Viv are the only two women to recognize and lament the pain of their losses, but they don’t share this with the group. That would not have been acceptable.

The nature of the friendship of these women is at the heart of Our Kind. How do they define “their kind”? They seem very uncomfortable with the idea of friendship and any sort of warm, emotional connection.

We were company, perhaps; women of a certain age with shared interests. But friends? It seems too intimate, somehow, wrong.

Despite the fact that these women spend parts of nearly every day together, especially after the births of their children, the narrator says,

… the day has simply passed the way days pass now — all of us together, not for companionship, exactly, or high regard, but because we’re in the same boat.

When it comes to spouses and partners, they feel that,

“Lover” is not a word in our lives, nor in the lives of anyone we know: It’s too animal, somehow; too raw. It suggests dime-store novels and intrigue, everything impractical.

As divorce, alcohol and deaths take their toll, these women are not the kind to ask for professional help or seek counseling, although some had seen therapists; but that was considered a passing fad, “…like our former passion for fondue, or our semester learning decoupage.” When the narrator/collective identity defines “their kind,” it is thusly:

But what kind are we? Yellowing pearls on a taut string: valued once but now too fussy. Grit when crushed..; we were fakes all along.

Our Kind is a novel that satisfies on many levels: the writing is detailed and evocative without being bloated and overdone; the form complements the novel and its themes, making the it a fine homage to Woolf and Mrs. Dalloway; the characters are engaging and memorable (I honestly was reminded of several people from my parents’ generation, who would be just a bit younger than these women). This would be a great read for young women — a reminder not to throw your life away, not to lose your identity.