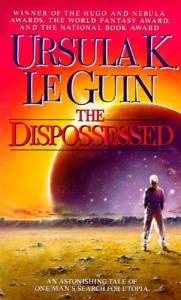

During the past few days, a couple of interesting stories crossed my screen and they are so perfectly related to my current review that they simply must be referenced. First came the #LikeAGirl campaign from Always, encouraging us to turn that pejorative expression into a compliment. Then came this story from NPR about women writers in science fiction: Women are Destroying Science Fiction and That’s OK — They Created It. As I have just finished Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic The Dispossessed, I must say that if you want to write science fiction/fantasy, you would do well to write #LikeA Girl.

During the past few days, a couple of interesting stories crossed my screen and they are so perfectly related to my current review that they simply must be referenced. First came the #LikeAGirl campaign from Always, encouraging us to turn that pejorative expression into a compliment. Then came this story from NPR about women writers in science fiction: Women are Destroying Science Fiction and That’s OK — They Created It. As I have just finished Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic The Dispossessed, I must say that if you want to write science fiction/fantasy, you would do well to write #LikeA Girl.

This Hugo and Nebula Award winning novel is about anarchy, brotherhood, individualism and the social compact. Set in the distant future on two planets (moons of each other) called Anarres and Urras, a brilliant Anarrasti physicist named Shevek is trying to develop a “General Temporal Theory,” which would reconcile the theory of sequency with the theory of simultaneity. In addition to wrestling with the intellectual problems presented by this task, Shevek must face his own inner conflicts and rebel against the system of his home planet that would ignore his work and against the “propertarians” of Urras who would try to use his ideas to empower themselves.

Much of the novel deals with political issues, which is why it has been referred to as “political science fiction” as well as utopian fiction. Anarres is a mostly desert planet that supports some marine life and a few plants. It was uninhabited by humans until 150 years ago when anarchist rebels from Urras, as part of their Settlement with the Urrasti government, moved there and set up an anarchic society called “Odonian” after the principles of martyred rebel leader Laia Odo. Anarres has since voluntarily isolated itself from Urras and all other planets and peoples except for occasional trade missions from Urras. The port in Anarres is walled off so there is no contact between the peoples. Thus for 150 years, the people of these planets have lived in ignorance and fear of one another.

The inevitable collision of these worlds is rooted in Shevek’s research. He is a brilliant physicist, and at the age of 20 published groundbreaking research. His advisor, Sabul, is instrumental in getting this work sent to the leading physicists in Urras, who are the only others capable of understanding the importance of Shevek’s work. Sabul is the leading physicist on Anarres, but what we and Shevek learn is that his expertise is limited and that he has claimed others’ ideas (including Shevek’s) as his own. Shevek’s intellectual isolation and desire for open communication with those on Urras who could understand and stimulate his research, coupled with his friend Bedap’s revolutionary ideas, become the catalyst for Shevek’s personal revolution as well as political unrest on Anarres and Urras.

Anarres is an “ambiguous utopia.” For 150 years they have managed to scratch out a living in trying circumstances by pitching in and living by admirable principles. And yet, a cost has been exacted that seems contrary to their idealistic aims. As Shevek says, “…the social conscience completely dominates the individual conscience…. We don’t cooperate — we obey…. We fear our neighbor’s opinion more than we respect our own freedom of choice.” When Shevek and his friends form their own publishing syndicate and open communication with Urras, the PDC (Production and Distribution Coordination council, which is not government but administers all production on Anarres) expresses opposition but cannot stop them. The PDC also protests the syndicate’s proposal to send someone to Urras to open communication. They cannot stop Shevek from going, but they could perhaps prevent his return.

Urras is a capitalist world dominated by the “1%”. It is a lush, fertile planet with plenty of everything. Shevek is overwhelmed by the excess (which Anarrasti refer to as “excrement”). His handlers on Urras put him in contact with the intelligentsia and political elites, and they closely monitor his movements. Shevek begins to feel as uneasy and isolated on Urras as he did on Anarres, and he learns that the Urrasti want him to provide his General Theory for them to use exclusively for their own profit. Meanwhile, war breaks out on Urras and unrest arises among the unseen (by Shevek) working class of the capital. The question is whether Shevek will be able to protect his idea, help the 98% in their struggle and somehow get back home again.

The structure of this novel is brilliant. Le Guin actually uses Shevek’s “sequency” and “simultaneity” in telling the story. Starting with Shevek’s contentious departure for Urras, chapters alternate between Shevek’s life on Anarres leading up to that moment, and his experiences on Urras leading to the novel’s thrilling conclusion. Past and present are simultaneous while events happen in sequential order. Much like the physics described in the novel, the plot brings the reader around in a circle, back to where we started and yet it is not the same spot. Le Guin’s worlds — Anarres, Urras, Terra, Thu and Hain — are complex places that contain both admirable qualities and undeniable flaws. No one place comes off as the “right” type of society or governance. And many of the problems that these worlds face are similar to those we face today. The fate of Terra, which is meant to stand in for our Earth, is especially frightening because it’s so plausible. The meeting between Shevek and the ambassador from Terra is one of the best scenes in the novel.

There are so many themes in this novel that could be discussed in a class. Le Guin provides much to discuss regarding women’s equality, political systems, economic systems, the rights of the individual and the needs of society, sexuality and relationships. The Dispossessed was published 40 years ago but is timely and relevant today. This is truly excellent fiction, sure to spark discussion and debate among those who read it.

*****

For the 2014 Cannonball Read, 50 of my 52 reviews will be of books written by women. I am doing this as part of the #ReadWomen2014 campaign and as a way to mark my upcoming 50th birthday. Among the books to be reviewed, I have decided to include a book written by a woman in the year I was born (1964), as well as for each subsequent 10 year anniversary of my birth. This is the second installment: 1974