Initially, I only gave this four stars because it was just such a difficult reading experience. And I don’t mean difficult as in skill level. I mean it in terms of emotional effort.

Initially, I only gave this four stars because it was just such a difficult reading experience. And I don’t mean difficult as in skill level. I mean it in terms of emotional effort.

I usually reserve my five star rating for those books that end with me fist-pumping in the air and running screeching around the room while my pores ooze out excitement and love, and this is not the sort of book that inspires that kind of reaction. I think this says a lot about the ways that I prefer to enjoy stories, and not really a lot about the quality of this book. Upon reflection, I couldn’t think of a single reason NOT to give this five stars, and the more I thought about the book (the more that I think about it still), the more I realized my refusal to award it five stars was entirely based on my inability (still) to acknowledge that the situations the people in this book face are real. They are really happening. Right now. All over the world. It’s not a happy thought at all, and even though it’s primarily how I use literature, happy is not necessarily the healthiest endgame for a narrative, especially one so concerned with something as important as poverty.

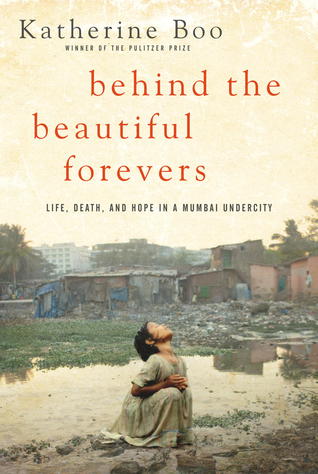

Behind the Beautiful Forevers is a nonfiction narrative set in and about the now non-existent slum community of Annawadi, which used to be located outside the Mumbai airport. At the time of this book, Annawadi was home to thousands of ‘squatters,’ many of whom had made it their home for decades after the originally marshy and unusable land had been ignored by the airport authorities who owned it. Katherine Boo — who had previously won a Pulitzer for her work on documenting poverty and disability, as well as a MacArthur “genius” award — upon marrying her Indian husband, became fascinated with the fast-growing economic and cultural conflicts taking place in modern India, where vast wealth and economic growth live side by side with economic disadvantage and corruption. She set out to document modern slumlife in India by doing field research for over three years. She spent these years following around a select group of Annawadi citizens in a concerted effort not to romanticize or misrepresent life in the slums.

Boo, like the classy journalist she is, is very careful not to overstate the ramifications of her findings, stating specifically that life in Annawadi is by no means representative of India, or of every poor community in the world. This book is very much a specific portrait of a specific place with specific people in it. It follows several main Annawadians — the wannabe slumlord; her daughter, who is about to the first Annawadian to graduate from college; the trash collector; the jealous one-legged woman who lives next door, etc. — and the level of detail Boo gives us places these people is more than enough for us to draw our own conclusions. And those conclusions are what is devastating. The whole thing is presented in Boo’s impeccable style, and honestly reads more like a novel than it has any right to, with the inciting event being a woman burning to death, the young man who is falsely accused of killing her, all set to the backdrop of the 2008 recession. I was compelled to finish it against my will.

But it’s shit like this that makes me think this is a book probably everyone should read:

“What was unfolding in Mumbai was unfolding elsewhere, too. In the age of global market capitalism, hopes and grievances were narrowly conceived, which blunted a sense of common predicament. Poor people didn’t unite; they competed ferociously amongst themselves for gains as slender as they were provisional. And this undercity strife created only the faintest ripple in the fabric of the society at large. The gates of the rich, occasionally rattled, remained unbreached. The politicians held forth on the middle class. The poor took down one another, and the world’s great, unequal cities soldiered on in relative peace.”

And this, too:

“In places where government priorities and market imperatives create a world so capricious that to help a neighbor is to risk your ability to feed your family, and sometimes even your own liberty, the idea of the mutually supportive poor community is demolished. The poor blame one another for the choices of governments and markets, and we who are not poor are ready to blame the poor just as harshly.”

I mentioned in my initial review that I am by no means a wealthy person. Having enough money is something that I struggle with on the regular, but reading this book was a wake-up call that even though I struggle, in many ways my life is still one of strong privilege, and like the people Boo documents in this book, I’m not entirely sure what I would become if I had to live like they do.

(Upon finishing, I also had a strong urge to abduct all the wealthy corporate CEOs of the world and force them to read this book, the motherfuckers. Another case of the people who most need to read this book never going to do so.)