I happened to be reading The Handmaid’s Tale when the story about the UCSB shooting spree hit the news. By now, most likely you’ve read that the shooter hated women because he couldn’t get a date and that he left behind a “manifesto” and many videos in which he presented his misogynistic ideas. In response, and as an empowerment for women, the hashtag #YesAllWomen has gone viral, with women and men speaking up and speaking out against the culture that creates men like the shooter. As Jeopardy champion and self-proclaimed nerd Arthur Chu wrote in The Daily Beast, the misguided notion of “entitlement” contributes to the rampant misogyny and violence against women that we are seeing today. He writes:

I happened to be reading The Handmaid’s Tale when the story about the UCSB shooting spree hit the news. By now, most likely you’ve read that the shooter hated women because he couldn’t get a date and that he left behind a “manifesto” and many videos in which he presented his misogynistic ideas. In response, and as an empowerment for women, the hashtag #YesAllWomen has gone viral, with women and men speaking up and speaking out against the culture that creates men like the shooter. As Jeopardy champion and self-proclaimed nerd Arthur Chu wrote in The Daily Beast, the misguided notion of “entitlement” contributes to the rampant misogyny and violence against women that we are seeing today. He writes:

“…the overall problem is one of a culture where instead of seeing women as, you know, people, protagonists of their own stories just like we are of ours, men are taught that women are things to “earn,” to “win.” That if we try hard enough and persist long enough, we’ll get the girl in the end. Like life is a video game and women, like money and status, are just part of the reward we get for doing well.”

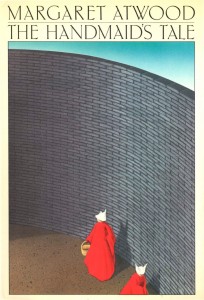

In Atwood’s dystopian novel, this twisted view of women and their purpose — as sexual objects primarily, as status symbols to be earned, existing solely for the purpose of procreation — has become the reality in Gilead, the despotic theocracy that has replaced the United States’ constitutional government. The tale’s narrator is a woman in her early thirties, one of the first wave of “handmaids,” i.e., women who are forced to become breeders for ruling elites who cannot have children of their own. We never know the woman’s real name; she is simply Offred (of Fred). Other handmaid’s are similarly named (Ofglen, Ofwarren). Handmaids are property and they are strictly regulated in their dress, social interactions, eating habits and all other activities. Women who aren’t handmaids fare just as poorly. “Wives” of commanders are part of the ruling elite and have many privileges but no political power; they participate in bizarre procreation rites with their husbands and handmaids, and they will raise the children born. “Marthas” are domestic servants, “Econowives” are wives of poor/low status men, “Aunts” serve the regime as the forces of handmaid indoctrination, and “Unwomen” are political prisoners sent to the worst places to work and die. All women fit into one of these categories of enslavement.

The novel tells the tale of Offred, her life before the revolution and now as a handmaid. In her flashbacks, we learn that she was the wanted daughter of a single mother who was very active in promoting women’s rights. She had a best friend Moira, who was rather unorthodox before the revolution and became a renegade after. She also had a husband and a daughter whose fates are painful for her to recall. Offred initially comes across as timid, defeated by her circumstances, but there is a part of her that can still remember the past and that longs to defy, to transgress. Her opportunity to do so comes from an unexpected quarter — her commander. Their relationship is supposed to be only sexual, but the commander also remembers a past and longs for something more. As Offred and the commander take more chances, one can sense the impending doom. Will Offred make it out of this alive? Will she be betrayed by the commander or by Wife Serena Joy (who sounds little like Tammy Faye Baker) or by one of the Marthas or by Nick the driver or by another handmaid?

The world Atwood has created for this novel is violent and disturbing, with Prayvaganzas (public group weddings where soldiers are awarded brides not of their choosing), Salvagings (public executions), the public wall where the bodies of traitors hang, the indoctrination of handmaids and the use of women to subjugate women. I think what frightens most is the sense that it really could happen. The novel was published in 1986, a time when we started hearing more debate about a woman’s right to control her own body and about taking back the night; when environmental concerns, particularly regarding nuclear energy, were making the news regularly; when the growing influence of the religious right was becoming evident in politics. We face the exact same problems today with rape culture and violence against women, fracking and the ensuing earthquakes and pollution, and rightwing nutjobs using the political system to impose their morality on the nation at large. The 1980s look tame in comparison. For me, The Handmaid’s Tale is even scarier than the books I reviewed by Christie, Jackson and du Maurier.