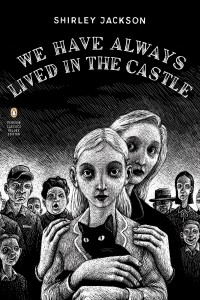

Shirley Jackson (1916-1965) was an American writer known for novels such as The Haunting of Hill House and short stories such “The Lottery,” which has horrified readers since 1948. To this day I am haunted by the short film version of “The Lottery” (with Ed Begley, Jr.!) which Sr. Mary Cabrini showed in my American Studies course in high school. The 1962 novel We Have Always Lived in the Castle is not exactly scary like Jackson’s other works, but it is disturbing and feels like a witch hunt story. While one character is an unbalanced murderer, it’s the “innocent” townspeople who are truly frightening.

Shirley Jackson (1916-1965) was an American writer known for novels such as The Haunting of Hill House and short stories such “The Lottery,” which has horrified readers since 1948. To this day I am haunted by the short film version of “The Lottery” (with Ed Begley, Jr.!) which Sr. Mary Cabrini showed in my American Studies course in high school. The 1962 novel We Have Always Lived in the Castle is not exactly scary like Jackson’s other works, but it is disturbing and feels like a witch hunt story. While one character is an unbalanced murderer, it’s the “innocent” townspeople who are truly frightening.

Merricat (Mary Katherine) and her sister Constance Blackwood live with their sickly Uncle Julian in a small New England village. Their home is a stately sort of mansion off the beaten path, and that’s how they like it. Constance, in her late 20s, never ventures off the grounds and does not like visitors. It has been 6 years since her parents, brother and aunt died suddenly after eating a dinner she prepared. Merricat, age 18-ish, ventures out once or twice per week for groceries and library books but hates the villagers, frequently imagining their horrible deaths. Merricat has odd patterns of thinking and pronounced obsessive compulsive behaviors, such as never entering her Uncle’s room and burying objects throughout the grounds as a protection for the home and their lifestyle. Their uncle Julian spends his days writing about the deaths of the rest of the family, trying to make sense of it. All is well, at least from Merricat’s point of view, until cousin Charles arrives without notice. Merricat hates him, seeing him as both a demon and a ghost whose presence must be purged, the house cleansed of his presence. While Constance surprisingly welcomes Charles, Julian and Merricat do not, and it becomes clear that Charles’ intentions toward them are not the selfless familial devotions that he claims. The impending showdown between Charles and Merricat has a sinister edge; one of them must go. Who will it be?

Merricat serves as our narrator, and given her questionable mental health, the reader is never quite sure if s/he is getting the truth. The villagers are, through her eyes, a hateful and jealous bunch, obsessed with her family’s history and resentful of their wealth and distance. Adults and children alike taunt Merricat when she makes her visits to town. At the final showdown between Charles and Merricat, the villagers’ true colors are revealed.

Jackson shows, sometimes with humor, how nasty and brutish life in a seemingly quaint small town can be. As with Christie’s And Then There Were None, what unsettles is the notion that average ordinary people such as ourselves can hide a dark side to the point that an unstable, murderous person can win your sympathy. This was a weird but fascinating read.