My hand is a human hand. My heart a human heart. My feet walk the earth to which our bones return. Directed by His voice, His hand, by the prompting and guidance of His spirit, what else was I to do? ~ Father Damien in a letter to the Pope

My hand is a human hand. My heart a human heart. My feet walk the earth to which our bones return. Directed by His voice, His hand, by the prompting and guidance of His spirit, what else was I to do? ~ Father Damien in a letter to the Pope

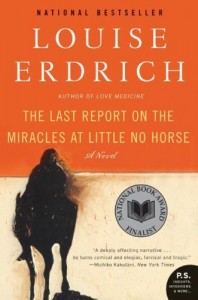

The Last Report on the Miracles at Little No Horse was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2001. I’ve reviewed two of Erdrich’s other novels — The Plague of Doves, which won a Pulitzer Prize and The Round House, which won a National Book Award. Erdrich is, without doubt, one of the best authors writing today. She introduces us to amazing characters who are flawed but beautiful. Erdrich combines humor, history, spirituality, and hard reality in her stories, and demonstrates that in Native American communities, the present is bound to the past.

This novel is the story of Father Damien Modeste, a Catholic priest who came as a missionary to an Ojibwe community called Little No Horse in North Dakota in 1912. One thing (and not the most important thing) that sets Father Damien apart from other missionary priests is that he is actually a she in disguise. The story begins in 1996, when Father Damien is well into his 90s. Father Jude Miller has been sent by the Vatican to investigate claims that a nun named Sister Leopolda (deceased) was involved in miraculous activity when she was at the convent in Little No Horse. Damien was well acquainted with Leopolda and through interviews that Father Jude conducts with Damien and others who knew Leopolda in Little No Horse, we learn not just the truth about Leopolda’s “miracles,” but the history of the community there, Father Damien’s past, and other miraculous activity that occurred among the Ojibwe.

Much of this novel focuses on the impact of missionary work and conversion efforts on Native American communities. When Damien arrives (and the story of how Agnes DeWitt becomes Father Damien the missionary is a fabulous tale), he learns quickly that trying to impose Western spirituality on an already existing rich native spirituality isn’t going to work. Damien starts writing letters to the Pope regularly in 1912, seeking advice and guidance that never comes. In one letter he writes, “The ordinary as well as esoteric forms of worship engaged in by the Ojibwe are sound, even compatible, with the teachings of Christ.” Damien sees much to admire in native spirituality and balks at forcing conversions and Christian morality (such as having only one wife) on the Ojibwe. This is where he and Leopolda, who was adamant about conversion, clash. As Damien tells Father Jude, “It all goes back to conversion, Father, a most ticklish concept and a most loving form of destruction.” Father Jude, in trying to learn more about the real Leopolda and her miracles, finds that many at Little No Horse, including Father Damien, don’t really want to talk about her. Damien reveals that Leopolda was his “hair shirt,” and “a continual scapular of annoyance.” When Father Jude suggests that her sin was the “overzealousness of one who burns with the Holy Spirit,” Damien replies, “Oh, she burned, all right…. She was a regular spiritual arsonist.”

When we and Father Jude learn the truth about Leopolda, we also learn that miracles and “passion” can take various, unexpected forms. The word “passion” comes up many times in this novel. As we learn from Father Jude, passions are stories of the saints, their lives and suffering for the faith. Passion comes from the Latin word for suffering, and there are many types of passion in this story. The question is, which forms of passion really demonstrate faith and goodness? In this vein, Jude and Damien have a very interesting discussion about sex outside marriage. Jude feels that it “hurts the order of things,” creating disorder and problems. Damien has generally been very forgiving of it among his flock and counters that, “Anything, though, of a large nature will create problems. The more outre forms of religious experience, for instance.” This is a direct hit at Leopolda and her behavior toward the Ojibwe.

In the end, this novel shows how painful conversion can be, whether we’re talking about what happened to Native Americans and their traditions or what happened to the religious men and women who were changed by their experiences in working with them. As always, Erdrich presents her themes and develops her plot in a tender and loving way that makes the punches of reality especially effective. One of the things I have loved about Erdrich’s novels is that her characters are so human, so complicated. None of them are two dimensional “types;” they are unique characters who can be selfless and yet make incredibly poor and hurtful choices. A good example of this is the tribal elder Nanapush. He is one of Damien’s best friends and can be deeply spiritual and wise, and yet also a thoroughly selfish wiseass. Erdrich includes wonderful tales of this Ojibwe community’s history that have the feel of magical realism, but she also shows the painful destruction of these communities through encroaching white western culture, religion, industry, and their own internal divisions. I imagine this book irritated a lot of conservative Catholics when it was published and would most certainly do so still today. I absolutely loved it.