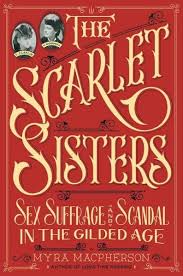

Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee (Tennie) Claflin were two sisters famous/infamous in American social and political circles starting in the 1870s. While most would think of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony when it comes to women’s rights, suffrage and reform, these sisters were renowned orators whose lifestyle fascinated and irritated the general public, especially men in power. They were from the wrong social class and espoused scandalous (for the time) views on sex, women, the poor and wealth. And they were linked to one of the most famous trials of the 19th century — the adultery trial of Henry Ward Beecher, esteemed minister and brother to Harriet Beecher Stowe of Uncle Tom’s Cabin fame.

Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee (Tennie) Claflin were two sisters famous/infamous in American social and political circles starting in the 1870s. While most would think of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony when it comes to women’s rights, suffrage and reform, these sisters were renowned orators whose lifestyle fascinated and irritated the general public, especially men in power. They were from the wrong social class and espoused scandalous (for the time) views on sex, women, the poor and wealth. And they were linked to one of the most famous trials of the 19th century — the adultery trial of Henry Ward Beecher, esteemed minister and brother to Harriet Beecher Stowe of Uncle Tom’s Cabin fame.

The sisters came from a life of poverty and a family business of hucksterism. Their father Buck was a snake oil salesman who prostituted his older daughters and forced Vicky and Tennie into fortunetelling and spiritualism — making contact with the world beyond and dead loved ones. One of the odd things about late 19th America was that religion/spiritualism was an area where women could and did lead. But Vicky and Tennie chaffed at their father’s domineering ways and made a break of sorts, setting out on their own. They were never completely free of their troublesome family, however, and their parents and siblings were often the cause of their greatest embarrassments.

The sisters were incredibly progressive for their time. They became the first female brokers on Wall Street, thanks to financial support from Cornelius Vanderbilt; they spoke openly and forcefully in favor of “free love,” which seems to have meant a variety of things, but for the sisters, it included the freedom to leave a loveless marriage; they promoted women’s equality and Victoria managed to get an audience before the Congressional Judiciary Committee to argue for the citizenship of women while the so-called leaders of the feminist movement watched in awe; and they wrote and acted on behalf of the working class. Tennie distinguished herself by being the first woman named colonel of a military regiment (New York’s 85th, the only black regiment in the state) and Vicky was the first woman to run for President on a ticket with Frederick Douglas.

While their interests and scope of activity were impressive, the two women also seem to have taken some views over time out of convenience and self interest. An example would be their promotion of free love, which is the topic that brought them the most attention and vilification. Readers might admire their courageous stance on sexual equality for women in the late 19th century, but in the early 20th century, they made a complete about-face and even went so far as to try to deny that they had ever made statements in support of free love. When the British Museum purchased for its library archives newspapers and other writings that contained Victoria’s ideas on free love (including tracts she had written herself), she sued them for libel (and lost).

MacPherson does an admirable job of wading through available resources. Given the strong feelings that the sisters evoked in both detractors and admirers, the researcher has to be very careful not to believe every bad (or good) thing written about them. Her coverage of the Beecher trial was especially well done. I had not been aware of the adultery charges against Beecher, but this was the sort of “trial of the century” that attracted the interest of all newspapers and all strata of society. MacPherson’s great strength is in showing how the political, economic, social, and sexual politics of the sisters’ age are so very close to our own. On the whole, while the sisters can seem dishonest, hypocritical and self-serving, one cannot help but admire their bold stance on social reform and their verve and fearlessness in promoting their ideas. Perhaps the worst that can be said is that they behaved like the powerful men of their (and our) age. And they did it surprisingly well given the political and social limitations placed on women.