Sci-fi has always been a dirty, filthy genre that no right-thinking author would pursue and no properly-educated reader would allow to sully his bookshelves. At least, that’s what my all English teachers told me.

Sci-fi has always been a dirty, filthy genre that no right-thinking author would pursue and no properly-educated reader would allow to sully his bookshelves. At least, that’s what my all English teachers told me.

So when proper literary authors dip their toes into sci-fi, it’s invariably interesting regardless of the quality of the outcome. And make no mistake, no matter what the pedigree of the author, this sort of literary sci-fi can run the gamut from amazing (Infinite Jest, certainly, or The Handmaid’s Tale) to downright awful (The Plot Against America, I’m looking in your direction… and on a side note, I wish I remembered who recommended American Pastoral to me, because I’d like to return the favor by taking a big, steaming dump on their welcome mat).

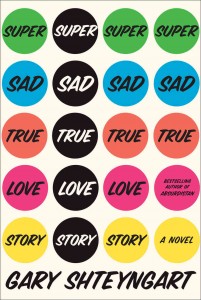

Gary Shteyngart’s Super Sad True Love Story represents a better-than average foray by a fairly Serious author into the part of the ideaspace best represented by spaceships and alien worlds. America is on the brink of utter collapse, and the government has reacted by wildly expanding the scope and mandate of its spying and social restriction powers, though there’s a peculiar whiff of the slapstick to it (misspelled signs, computer errors, many of the hallmarks of Bureaucracy In Decline). People’s credit scores, not to mention their “fuckability” scores, are a matter of public record and enthusiastic discussion (especially about the latter). Fashionable teenagers wear “onionskin” transparent jeans and actively resist the concept of having non-technologically-mediated interactions. Given the 2010 publication date, one can only assume that the book was written amidst and during the immediate aftermath of the 2008 financial meltdown, and it shows.

Against this backdrop we meet Lenny, late-thirtysomething son of Russian immigrant parents. He’s some sort of pitchman/salesman/something for a company selling kinda dodgy life extension surgeries to the super-wealthy. On extended working sabbatical in Rome, he meets Eunice, early-twentysomething daughter of Korean immigrant parents. She’s a spunky, anorexic perma-student who’s considerably wilier in the ways of this postmodern world than poor beleaguered Lenny. Soon enough, they’re both back in New York City and intermittently dating. And then things happen and stuff. It’s all a bit wandering, whether the foreground action with our main characters or the background action with the collapsing supernova that is the United States government.

Lenny sees in Eunice a chance to hang onto his waning youth. It’s less clear what Eunice sees in Lenny, unless it’s a barely-expressed need to escape her abusive father. There’s a whole children-of-immigrants thing here that I will confess doesn’t resonate particularly strongly with me, but then again I’m not the child of immigrants. Having known a few in my time, I’ve always been mystified by the relationship between first and second generation immigrants, and, to be quite frank, the seemingly frequent emotional and occasional physical abuse that such relationships can manifest. I’m not making a value judgment here, or at least I’m trying not to, only pointing out that uprooting your family, moving to an entirely different country, leaving behind the values and mores of your old society, and watching your children embrace the values and mores of your new society, that can’t possibly be easy, or simple, or emotionally uncomplicated. Shteyngart himself is the son of Russian immigrants, and thus one presumes that this conflict between first and second generations is one rather close to his heart. Certainly he depicts such relationships well (though Eunice’s abusive father is a woefully underdrawn character), it was just difficult for me to empathize, more or less.

If you’re wondering “hey, didn’t you mention sci-fi at the top of the review?”, the answer is that, much like with the book, the mention of sci-fi works more as a hook than as a core story element. Despite, for instance, Shteyngart giving mobile phones a Russian-sounding new name (apparati), they function in much the same way. It’s very near-future sci-fi, or more accurately it’s the trappings of near-future sci-fi welded (occasionally awkwardly) to a postmodern satire masquerading as a love story. Overall the effect was like watching a David Foster Wallace tribute band. Not a bad thing, necessarily. Just, y’know, super sad.