Imagine this. You’re a college student from a fairly prosperous family. You know things are starting to go wrong in your country, but your position in life shelters you from the profoundly bad shit that’s going down. You have a girlfriend, but social mores and the difference in your stations mean that the most you’ve ever done is hold her hand during late-night walks down unlit streets. But then, your family begins to run out of money, long after less fortunate people have already begun to succumb to famine. Of course, you don’t dare talk about this with anyone, as even your best friend might be an informer for the state police (in fact, such informers are often encouraged to complain about the government, hoping to get people to join in such criticism), and people who criticize the Dear Leader have a tendency to disappear in the night, only to end up with a life sentence in a labor camp, or worse.

Imagine this. You’re a college student from a fairly prosperous family. You know things are starting to go wrong in your country, but your position in life shelters you from the profoundly bad shit that’s going down. You have a girlfriend, but social mores and the difference in your stations mean that the most you’ve ever done is hold her hand during late-night walks down unlit streets. But then, your family begins to run out of money, long after less fortunate people have already begun to succumb to famine. Of course, you don’t dare talk about this with anyone, as even your best friend might be an informer for the state police (in fact, such informers are often encouraged to complain about the government, hoping to get people to join in such criticism), and people who criticize the Dear Leader have a tendency to disappear in the night, only to end up with a life sentence in a labor camp, or worse.

Desperate to escape, hoping to go somewhere to make some money that you can send home, you pay a smuggler to get you across the border. Despite a lifetime of propaganda claiming otherwise, you find that people in the neighboring country are not starving, they’re not savages bent on destruction. In fact, their dogs eat better than your family did. You’re encouraged that you might have found a path to a better life. But the authorities back home catch wind of your desertion, and your sisters, your beautiful sisters who never said a treasonous word i their lives, are arrested and sent to a labor camp, where they will work until they die.

Here’s another one. You are starving to death. Worse, your children are starving to death. Legally you can only buy food from government stores, whose shelves have been empty for months. The only place to buy food is on the black market, and you’ve long since run out of meager possessions to sell for shabby balls of cornmeal containing more stalk and husk than kernel. You spend hours combing the fields and hills near your home for edible roots and plants, but those are becoming increasingly difficult to find because all your neighbors are starving to death too. You keep trying to supplement your diet with grasses and leaves, but you’re getting weaker, and your children are showing clear signs of severe malnutrition.

Left with no options, you climb a nearby telephone pole and strip the copper off the lines. After all, the system has been down for over a year, it’s not like anyone is going to miss a few feet of copper wiring. With this copper you’re able to postpone the inevitable, buy just enough food that it’s only next month, or the month after, that your children finally succumb to famine. Some time later, your neighbor informs the local commissar that you have stolen state property, for which you are briefly tried and summarily executed by firing squad.

Try this one on. You’re a young man in Japan-occupied Korea, circa 1945. Suddenly, Japan withdraws its forces as WWII comes to a close. Equally suddenly, a couple guys halfway around the world decide to arbitrarily cut your ancient, fairly homogenous country in half due to geopolitical realities. By accident of geography, you happen to live south of that arbitrary line. A few years later, spurred in large part by ideological conflict spawned by this arbitrary line, the strange historical anomaly known as North Korea launches a brutal invasion of the south. You take up arms to defend your home, as do practically all men your age. Years of fighting follow, and by the end of the war the Korean antagonists have been subsumed into a clash between the United States and Communist China. However, you are still alive, still fighting for your home.

Two weeks before an armistice is signed, you are captured by the Chinese and delivered to your one-time countrymen in North Korea. You spend weeks in a POW camp with no access to the outside world. Your family has no idea you are still alive, nor does your army unit. Then one day, you’re bundled into a truck along with other POWs and driven to the mountainous north of North Korea and told that you are now a miner. You will be given North Korean citizenship, but you, your children, and your grandchildren will always be second-class citizens, always suspected of ideological treason, destined to eking out a life on the lowest rungs of North Korean society. You will die as an expendable miner in a country not your own. You will never see your family again.

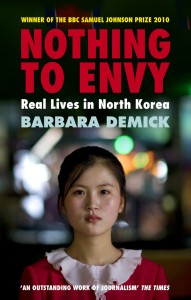

Welcome to the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea, a strong contender for most horrifying place on earth. Barbara Demick, at the time the LA Times bureau chief in South Korea, combines reportage, interviews of hundreds of defectors, and personal trips to North Korea, to paint a picture of a country that combines the worst qualities of Auschwitz and 1984. Immaculately tended pictures of the Great Leader, but no medicine. A nationwide secret police apparatus, but no jobs. A nuclear weapons program, but no food. The ground-level effects of the famine of the mid-to-late-90’s is rendered in heartbreaking detail, as even the staunchest supporters of the regime begin to slowly see the light as their families starve to death around them. Demick tells the story of post-war North Korea through the eyes of six people: star-crossed lovers, a patriotic matriarch, her rebellious daughter, a street urchin, and a pediatrician, all of whom managed to escape the tidal pull of their terrifying homeland, though not without cost.

Nothing to Envy is not exactly an easy read, but it is a fascinating one. North Korea might as well be on a different planet. The system is so controlled, the populace so cowed, the privation so universal, it’s almost like scenes from a previous century. As a history buff, I knew the broad strokes of the last sixty years on the Korean peninsula, but certainly not in this level of detail. Demick sketches in some history along with the personal stories and keeps the balance between the two strong. Ad while describing this book as “hard to put down” seems a bit disgusting, like it’s some Dan Brown beach read, I felt myself almost compelled to keep reading, if only to reassure myself that it was possible for people to escape this brutal, horrifying tyranny. It is, but at immense physical and emotional cost. And as long as a gang of psychopaths continue to rule over the 23 million people of North Korea, this will remain sadly true.

EDIT — I completely missed that genericwhitegirl reviewed this as well (literally a day before I did). Check out her considerably more comprehensive review here.